Contents of Article

Imagine various relationships you have with other people: sometimes we feel understood and our inner meanings of the mind are seen and respected. Other relationships may be more challenging, and the inner reality of our feelings and thoughts are unseen and disrespected. We send out communication to another person through the energy of our words and by way of our nonverbal expressions that can be heard and seen, but the other person does not create informational meaning from these energy signals. We feel disconnected, misunderstood and alone. The nature of our relationships is directly shaped by how energy is exchanged and information is created in this sharing of energy and information flow.

Siegel, 2012, p. 2.2

Born from and into relationships we cannot escape the susceptibility that comes from a life embedded and impacted by those who surround us. That we are an embodied representation of all the intergenerational interactions that came before us and an embodied configuration for the intergenerational interactions that will follow us (Clarkson, 2003; Siegel, 2012). Designed into our Divine sense of being (Genesis 2), this interactional interdependence is a complex fractalated phenomenon that holds the potential for reciprocating well-being and, by default the potential for antagonistic ill-being. But what is it about this fractalated phenomenon that holds the potentiality of The Divine (Balswick et al., 2016) and indeed, what is it about this phenomenon that makes it the most crucial factor in the therapeutic relationship (Norcross, 1999)? Whilst there is a myriad of possible answers provided by a myriad of thought schools, I propose that, in accordance with Gelso’s (2019) integrative conception of the therapeutic relationship and an Interpersonal Neurobiological perspective (Siegel, 2010 & 2012), it is the transcendent energy and information flow within and between the Self and the Other that holds this potentiality. More specifically, it is the manner by which this energy and information is shared, received, expressed, and reciprocated that holds the key to therapeutic change (Balswick et al., 2016; Gelso, 2019; Romans 12; Seigel, 2012). Such a manner, and indeed what shall be highlighted hereon in, includes an awareness of the real relationship (vulnerability) and the working alliance (availability) as they impact the dynamic process wherein vulnerability meets availability in either integrative or disintegrative potentiality. This concept shall be highlighted through three differentiated aspects 1) vulnerability and the being brain, 2) availability and the doing brain, plus 3) the interwoven relational realm; each emphasised by my own therapeutic and not so therapeutic experiences of such aspects.

Vulnerability and the being brain: The ever-emerging real relationship

Who I am, who I see you as; who you are, who you see me as

Though not a means unto itself, the real relationship is an ever-emerging facet within the overarching therapeutic relationship that has the potential to epitomise the authentic characteristics of both the Self (client) and the Other (therapist) (Clarkson, 2003; 1 Corinthians 12; Gelso, 2019). Such epitome occurs only to the extent that the Other mindfully acknowledges and embodies the energy and information flow that inherently exudes our sense of being (Balswick et al., 2016; 1 Corinthians 2; Gelso, 2019; Siegel, 2012). And, with acknowledgement and embodiment appropriately discloses a level of vulnerability that emanates a sense of safety, predictability, and meaning through its realness (Van der Kolk, 2018; Satir, 2013). Indeed, to the extent this vulnerability is intentionally used for benevolence (Matthew 25:34-40; Satir, 2013), is the degree by which the Other holds the potentiality to break through the unconscious resistance of the Self’s false perceptions and interpretations of the Other (Gelso, 2019; Siegel, 2010): the Self can receive and, in turn, reciprocate the same level of vulnerability (Clarkson, 2003; Gelso, 2019; 2 Corinthians 12:9).

Such ever-emerging real relationship is nevermore exemplified than within my own therapeutic experiences. Through two paradoxical encounters that ran parallel to each other over the course of this year, I have come to an overt knowing of how impactful domains of worldview (Aberbethy & Lancia, 1998; Peteet, 2013; see Appendix A – points 5, 11; see Appendix B – point 8), culture (Asnaani & Hoffman, 2012; Goh et al., 2012; see Appendix A – point 5; see Appendix B – point 8), attachment history (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2013; Schore, 2014; see Appendix A – points 8, 10, 31; see Appendix B – points 4, 7, 16, 26, 31), and personal proclivities (Siegel, 2012; see Appendix A – points 12, 20) are within the real relationship. Furthermore, I cannot negate the importance of how these domains are portrayed person-to-person (Clarkson, 2003) and vitally that this is affected by, and in turn affects implicit transferal experiencing (Clarkson, 2003; Gelso, 2019; Skourteli & Lennie, 2011).

As a white-privileged nearly 40-year-old woman enculturated into a Dutch-Australian Christ-centred (albeit untraditionally so) family who has a rich history of European travel followed by interpersonal trauma, I am well-aware that some of my personal proclivities (Siegel, 2010) often cause discombobulation within me. When circumstances are ripe for it, this discombobulation arises and propagates the sometimes anxious and fearful sides of me to perceive the Other not as they are but instead as an amalgamation of my past interpersonal interactions (Gelso, 2019; Schore, 2014; see Appendix B – points 7, 10, 11, 16), my expectations and anticipations (Clarkson, 2003; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2013; see Appendix A – point 12, ; see Appendix B – points 1, 5, 9, 13, 15, 29, 31), and the neurobiological mechanisms that pertain to a sense of safety (Gelso, 2019; Porges, 2018; Schore, 2014). Such is never more true than the potentially unreal, negatively valenced (Gelso, 2019) perception I formed of Therapist C (see Appendix B) and the seemingly genuine perception I formed of Therapist G (see Appendix A). These vastly differing experiences were paradoxical encounters of sensing salient insecurities that perpetuated resistances vs sensing salient security that broke through resistances (Gelso, 2019).

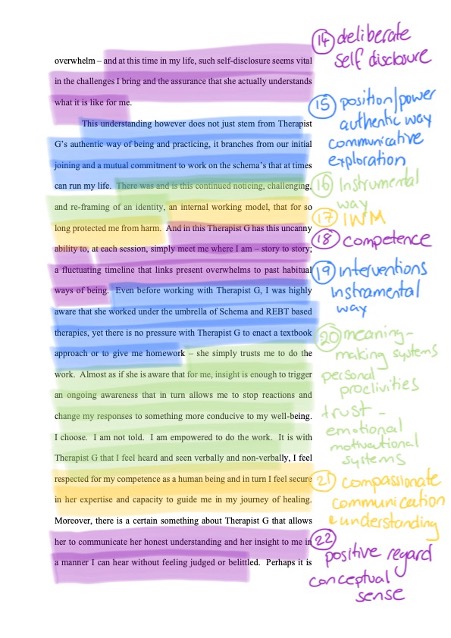

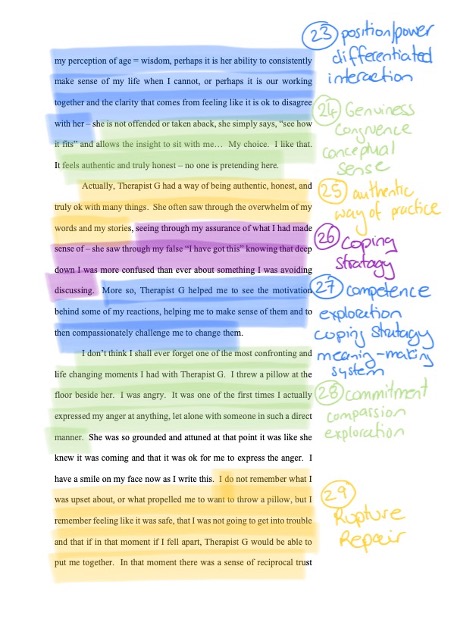

My perception of Therapist C, even now knowing that the relationship had a deep dimension of transference, was one that triggered danger. It was a perception where a lack of implicit self-disclosure and explicit dismissal of requests for self-disclosure contributed to an incongruence that tapped into my hidden sense of anticipated rejection (Audet & Everall, 2010; Rowan & Jacobs, 2002; see Appendix B – points 5, 9, 29, 31). There was no real sense of who she was, anywhere, and this felt incongruent and disempowering to me (Satir, 2013; see Appendix B – points 3, 6, 10), almost as if I were the only one there being vulnerable – which somehow left me struggling to share. This perception is a stark contrast to Therapist G and her willingness to, in authentic implicit and explicit vulnerability, disclose aspects of herself. Such aspects included Therapist G’s Christianity, her enculturated experiences, and her reformed sense of self that seemingly impacted her ability to compassionately understand me (see Appendix A – points 13, 15, 21, 28). There was a depth to Therapist G that consistently had empathy, constancy, and honesty with boundaries (Gelso, 2019), a warmth that created a sense of safety – a space that felt authentically connecting and where my vulnerabilities felt welcomed with care.

Such stark contrast between warmth and emptiness highlights the imperative nature of congruent authenticity: knowing the Other as a therapist with an embedded personal and professional identity. Someone who mindfully embodies and discloses a level of vulnerability that emanates a sense of safety, predictability, and meaning through its realness. A realness that transcendently develops and strengthens the potential of the energy and information flow within and between the Self and the Other (Gelso, 2019).

Availability and the doing brain: The allied agent of change

How I am, how you are, and how we reasonably bring ourselves to do the ‘work’

Just as the real relationship is not a means unto itself, so too the working alliance does not stand in isolation. Yet in contrast to the ever-emerging real relationship, the working alliance is an Other (therapist) instigated and Self (client) agreed upon use of the transcendent energy and information flow. Such deliberate use depends on a reasonable level of availability from both the Self and the Other (Clarkson, 2003; Gelso, 2019). Paradoxically however, whereas vulnerability’s absence merely denigrates a real relationship, availability’s absence destroys an allied collaboration between the Self and Other (Gelso, 2019). Thus, an effective collaborative alliance requires a methodical joining that manifests a reciprocating relational vector unique for the Self that desires change (Balswick et al., 2016; Clarkson, 2003; Gelso, 2019; Teyber & Teyber, 2017). Moreover, the extent that such a methodical joining considers and utilises elements that the Other is objectively aware, is the extent to which continued collaboration propels forward movement of change (Gelso, 2019; Proverbs 18:15-16; Proverbs 19:2). Such objectivity includes the evidence-based theoretical known whilst holding it alongside the Self’s subjective experience of knowing (Siegel, 2012; Proverbs 3; Philippians 4).

Such is exemplified by my therapeutic experiences; one in which the Self and the Other collaborated and re-collaborated on the nature of awareness and intentional change, and one in which there was a distinct absence of collaboration that went amiss from the Self and the Other’s awareness. These diverse experiences were based highly upon the impactful domains of position and power (Rowan & Jacobs, 2002; Satir, 2013; see Appendix A – points 2, 3, 4, 13, 15, 16, 19, 23, 25; see Appendix B – points 12, 17, 20, 21, 24), commitment and competence (Clarkson, 2003; Gelso, 2019; Teyber & Teyber, 2017; see Appendix A – points 1, 5, 7, 9, 18, 22, 24, 27, 28; see Appendix B – points 10, 12, 15, 19, 25, 28), Other’s moderated communicative exploration (Schore, 2014; see Appendix A – points 7, 15, 21, 27, 28, 30; see Appendix B – points 20, 24), as well as the Other’s consistent use of conceptual sense (Gelso, 2019; Siegel, 2010; see Appendix A – points 22, 24, 30; see Appendix B – points 10, 12, 15). Significantly here, I cannot negate the importance of how these domains are shared and received, and vitally that this is affected by, and in turn affects, resonance and resistance, rupture and repair (Clarkson, 2003; Gelso, 2019; Schore, 2014; Seigel, 2010; Teyber & Teyber, 2017).

Knowing what I know now, I might not have stayed with Therapist C for so long. Yet perhaps that is the journey of learning I needed. It seems, as aforementioned, that the expectations and anticipations I have of therapists, or had with both Therapist C and Therapist G, are not just based in or on my past interpersonal interactions. These experiences are based in my history of education and my determination to understand who I am. There is a level of knowing within me that is sensitive to the way Others non-verbally communicate, an attuning in me that seeks authenticity and honesty. It is something that often leaves me questioning intentions when non-verbals do not match verbal expressions. A seeming dimension of self-protection that perceives danger in what is not congruent, an embodied fear that signals the threat of subversive control and power (Satir, 2013; see Appendix B – points 3, 6, 25). This is in contradiction to a congruent use of personal and professional expression that signals the safety of freedom and equality (Rowan & Jacobs, 2002; see Appendix A – points 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9). Maybe I perceived what was not there, maybe Therapist C did not have the capacity to take responsibility for the therapeutic process (Clarkson, 2003; Gelso, 2019), or perhaps it was a combination of both that led to continued ruptures without repair (Gelso, 2019). Regardless, when I sat with Therapist C I felt unprotected and untrusted – I was the one with the issues, I was the one who needed an aim, a more overt intention, and that I was someone who needed more competence in life – everything about Therapist C’s way of therapy had a thinking, doing, fixing energy to it. This predominantly instrumental way of doing distinctly lacked flexibility, honesty, respect, trustworthiness, warmth, confidence, creatively, compassion, and care (Peteet, 2013; Rowan & Jacobs, 2002; see Appendix B – points 17, 19, 20, 24, 27); Therapist C distinctly seemed to lack an ability to convey interest in who I was as an emotive being who had freedom, the desire to take responsibility toward change, and expansive Self-potentialities (Hoffman, 2007). This formed perception left me unavailable and resistant to the motivation I generally find is entirely innate within me (Clarkson, 2003; 2 Corinthians 12:9; Jeremiah 29:11).

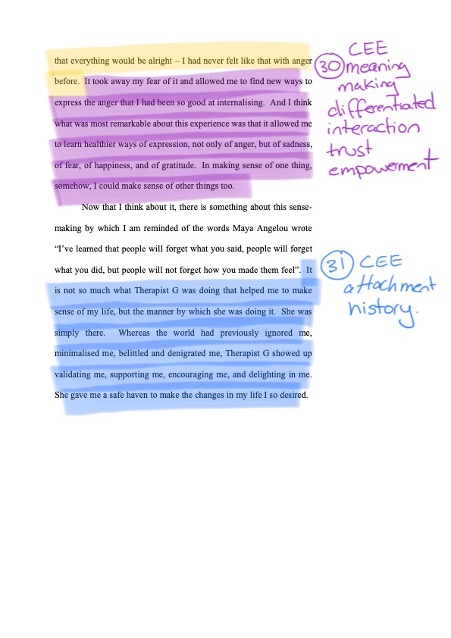

As before, I am aware that this perception is in stark contrast to my experience with Therapist G which was an experience of an authentic use of self (Rowan & Jacobs, 2002) that provided safety through consistent empathy, unguarded congruent verbal and non-verbal communication, and a level of mutuality that cultivated differentiated, yet integrated interaction (Satir, 2013; Siegel, 2012; see Appendix A – points 9, 23, 30). Therapist G consistently held in presence, was resonantly attuned, and allowed for misunderstandings to be expressed and resolved: there was no expectation of being better or doing something I did not want to do, and because of that there was trust and empowerment (Clarkson, 2003; Gelso, 2019; Satir, 2013; Siegel, 2010; Teyber & Teyber, 2017). There was a level of allied collaboration that assisted me in making sense of the non-sensical (Cozolino, 2002); it was a level of collaborated awareness within and between Therapist G and I that seemed almost transpersonal, something that went beyond the here-and-now and stayed with me (Rowan & Jacobs, 2002). An availability that offered strength I could call upon when I needed it (Philippians 4:3).

Significantly, this availability highlights the importance of the intentional mindful use of the vulnerability that exists in the real relationship as it pertains to the collaborative alliance in the manifestation of a reciprocating relational vector unique for the Self that desires change. This enigmatic vector unifies the transcendent energy and information flow within and between the Self and the Other, magnifying its diverse potentiality for both the Self and the Other.

Where vulnerability meets availability: The interwoven relational realm

The enigmatic emergence of uniqueness and unity

Colliding head-on in the juxtaposition between vulnerability and availability is the enigmatic emergence of uniqueness and unity – whether in a reciprocity of well-being or in an antagonism of ill-being. In its most optimal form (i.e., reciprocating well-being) when the flow of transcendent energy and information within and between the Self and the Other is (according to contextual conditions) vulnerable and available there is an enigmatic emergence of uniqueness and unity; a transpersonal togetherness that opens a timeless space for change (Balswick et al., 2016; Colossians 3:12-17; Schore, 2014). This is an interwoven relational realm where uniqueness and unity come together in resonate trust, and the potentiality of The Divine is accessed in an unfolding of the reflected imago Dei (Balswick et al., 2016; Ephesians 2:13-22; Genesis 1:27; Schore, 2014). Conversely, in its less-than-optimal form (i.e., antagonistic ill-being), when the flow of transcendent energy and information within and between the Self and the Other is resistant to vulnerability and/or availability, there is a distortion of transpersonal togetherness whereby the Self subconsciously finds replications of interpersonal patterning from the past, pulls them into the present, and shapes reality in an attempt to maintain and perpetuate internally known status quos (Clarkson, 2003; Gelso, 2019; Schore, 2014). And, in unmonitored, unmodified circumstances a simultaneous distortion can befall the Other in a reaction that similarly attempts to maintain and perpetuate such status quos (Clarkson, 2003; Gelso, 2019; Schore, 2014). This form of latency serves to protect each unique being yet ironically, if unseen, creates an antagonising abstraction where neither the Self or the Other can utilise The Divine’s potentiality that rests within the interwoven relational realm (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2013; John 14:26). Thus, it is imperative that the Other intentionally attunes to latent forms of protection through a present and aware monitoring and modifying (Satir, 2013; Siegel 2010) of the Self’s Internal Working Models (IWM; Schore, 2014; Skourteli & Lennie, 2011; Teyber & Teyber, 2017; see Appendix A – point 17; see Appendix B – points 4, 18, 22, 24, 30, 33), predominate coping strategies (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2013; Teyber & Teyber, 2017; see Appendix A – points 1, 26, 27; see Appendix B – points 27, 29), as well as the Self’s emotional-motivational meaning and sense-making systems (Cozolino, 2002; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2013; see Appendix A – points 20, 27, 30; see Appendix B – point 30). And, if done in benevolent efficacy with care toward unique expression and united reciprocity such monitoring and modifying of the interwoven relational realm creates a Corrective Emotional Experience (CEE; Gelso, 2019; Goldfried, 2012; Teyber & Teyber, 2017; see Appendix A – points 30, 31) rather than a re-enactment of the Self’s past (Teyber & Teyber, 2017; see Appendix B – points 31, 34).

With this in mind, and knowing that such monitoring and modifying of the Other is hard to exemplify directly, perhaps it is suffice to say that I am aware that the difference between Therapist G and Therapist C resided in their differing abilities to truly pay attention to how we were interacting in each session. That is, their differing abilities to see the unspoken transcendental relational aspects, to seek opportune moments and gently approach them with compassion and curiosity, and to work with me in making sense of who I am – moment-to-moment, context-to-context. Perhaps this difference stemmed from experience, perhaps it stemmed from my perception of Therapist G as a mother-figure and my perception of Therapist C as incongruent. Yet for the most part I believe what made Therapist C stumble was the inability to provide a secure base for exploration, to see beyond my many words and confusing stories, to hold and reflect affective elements, to give clarity to my subjective experiencing, and the inability to seek my input or to follow through on her interventions (Skourteli & Lennie, 2011; see Appendix B – points 21, 25). Ultimately, Therapist C was unable to provide the foundations for unique vulnerability and united availability, thus opening a Pandora’s box rife to enact my past interpersonal patterning and became discombobulated in distorted perceptions of our transpersonal togetherness (Gelso, 2019; Schore, 2014; Skourteli & Lennie, 2011). Whereas Therapist G was able to empathetically attune to my IWM, my coping strategies, and my need to make emotional sense of the many confusing aspects of my life and how they replay through my internal or external reactions and to compassionately challenge them – Therapist C was not. The result? Therapist C is no longer my therapist.

Conclusion

It took me a while to figure out why Therapist G could break through my initial resistances collaborating with me in an intentional movement toward integrated change. Yet it took me even longer to fathom why I formed such a negatively valenced perception of Therapist C that stagnated in disintegrative discombobulation. In the end the answer was complex, multidimensional, yet ironically so simple: vulnerability, availability, and an interwoven relational realm. Indeed, where Therapist C was guarded and seemingly disengaged, Therapist G was present and attuned. Therapist G cut through my resistances with resonance, I felt seen and heard, comforted and connected – there was a transpersonal togetherness that opened a timeless space for interactional interdependence and thus reciprocating well-being. This was a space where a uniquely unified flow of energy and information within and between the Self and the Other held potentiality; this was a space where Therapist G continually monitored and modified the manner by which this flow was uniquely shared and received, unified in expression and reciprocation. This was an interwoven relational realm where uniqueness and unity came together because of vulnerability and availability. A realm of resonate trust whereby the potentiality of The Divine was accessed in an unfolding of the reflected imago Dei – “and you will know the Truth, and the Truth will set you free” (John 8:32).

References

Abernethy, A. D., & Lancia, J. J. (1998). Religion and the psychotherapeutic relationship: Transferential and countertransferential dimensions. The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 7(4), 281-289.

Asnaani, A., & Hofmann, S. G. (2012). Collaboration in multicultural therapy: Establishing a strong therapeutic alliance across cultural lines. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(2), 187-197.

Audet, C. T., & Everall, R. D. (2010). Therapist self-disclosure and the therapeutic relationship: A phenomenological study from the client perspective. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 38(3), 327-342.

Balswick, J. O., King, P. E., & Reimer, K. S. (2016). The reciprocating self: Human development in theological perspective (2nd ed.). InterVarsity Press.

Clarkson, P. (2003). The Therapeutic Relationship (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Cozolino, L. (2002). The neuroscience of psychotherapy: Building and rebuilding the human brain (Norton series on interpersonal neurobiology). W. W. Norton & Company.

Gelso, C. J. (2018). The therapeutic relationship in psychotherapy practice: An integrative perspective. Routledge.

Goh, M., Skovholt, T. M., Yang, A., & Starkey, M. (2012). Developing habits of culturally competent practice. In T. M. Skovholt (Ed.), Becoming a therapist: On the path to mastery (pp. 79-87). John Wiley & Sons.

Hoffman, L. (2007). Existential-Integrative psychotherapy and God image. In G. L. Moriarty & L. Hoffman (Eds.), God image handbook for spiritual counseling and psychotherapy: Research, theory, and practice (pp. 105-137). The Haworth Pastoral Press.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2013). Attachment orientations and meaning in life. In J. A. Hicks & C. Routledge (Eds.), The experience of meaning in life: Classical perspectives, emerging themes, and controversies (pp. 287-304). Springer Science & Business Media.

Norcross, J. (1999). The therapeutic relationship. In B. L. Duncan, A. Hubble, & S. Miller (Eds.), The heart & soul of change: Delivering what works in therapy (1st ed., pp. 113-141). American Psychological Association.

Peteet, J. R. (2013). What is the place of clinicians’ religious or spiritual commitments in psychotherapy? A virtues-based perspective. Journal of Religion and Health, 53(4), 1190-1198.

Porges, S. W. (2018). Polyvagal Theory: A primer. In S. W. Porges & D. Dana (Eds.), Clinical applications of the Polyvagal theory: The emergence of polyvagal-informed therapies (pp. 50-72). W. W. Norton & Company.

Rowan, J., & Jacobs, M. (2002). The therapist’s use of self. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

Satir, V. (2013). The therapist story. In M. Baldwin (Ed.), The use of self in therapy (3rd ed., pp. 19-25). Routledge.

Schore, A. N. (2014). The right brain is dominant in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 51(3), 388-397.

Siegel, D. J. (2010). The mindful therapist: A clinician’s guide to mindsight and neural integration. W. W. Norton & Company.

Siegel, D. J. (2012). Pocket guide to interpersonal neurobiology: An integrative handbook of the mind (Norton series on interpersonal neurobiology). W. W. Norton & Company.

Skourteli, M. C., & Lennie, C. (2011). The therapeutic relationship from an attachment theory perspective. Counselling Psychology Review, 26(1), 20-33.

Teyber, E., & Teyber, F. (2016). Interpersonal process in therapy: An integrative model. Cengage Learning.

van der Kolk, B. (2018). Safety and reciprocity: Polyvagal theory as a framework for understanding and treating developmental trauma. In S. W. Porges & D. Dana (Eds.), Clinical applications of the polyvagal theory: The emergence of polyvagal-informed therapies (pp. 27-33). W. W. Norton & Company.

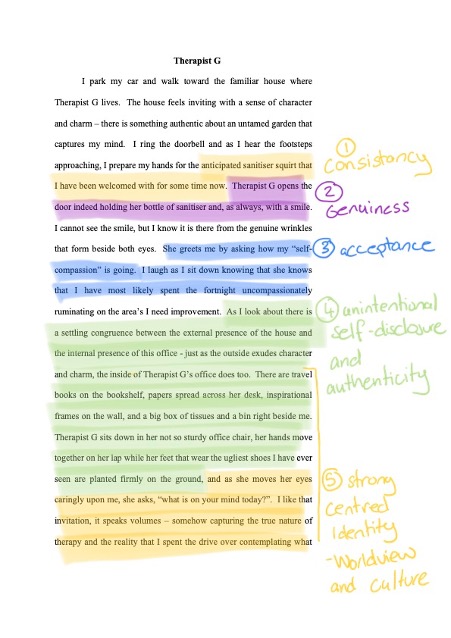

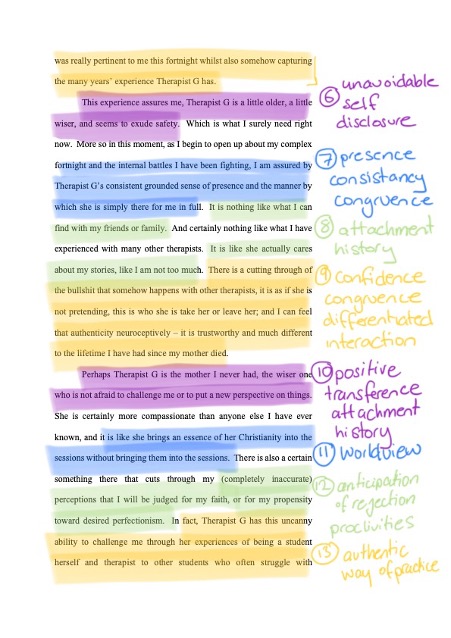

Appendix A

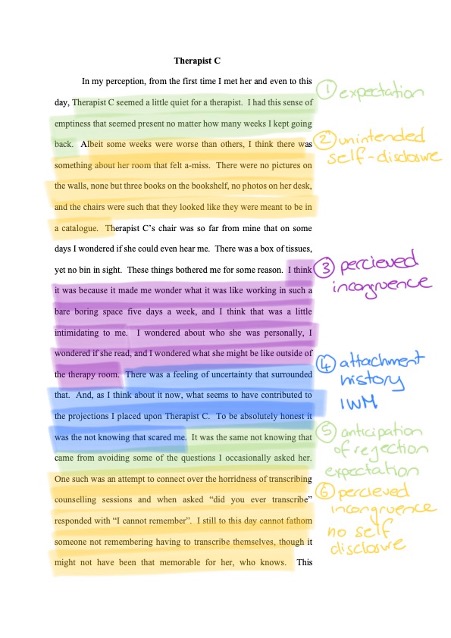

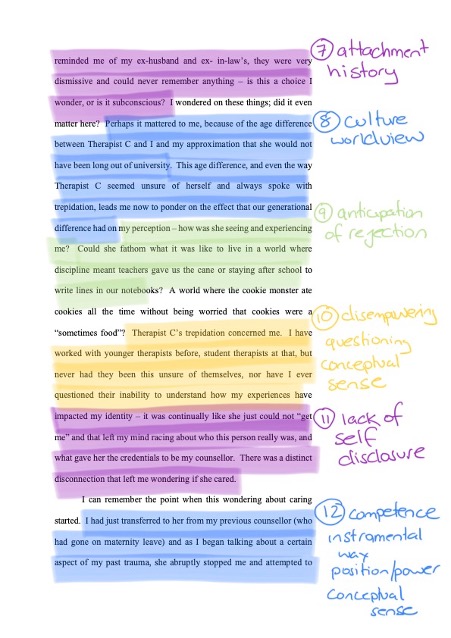

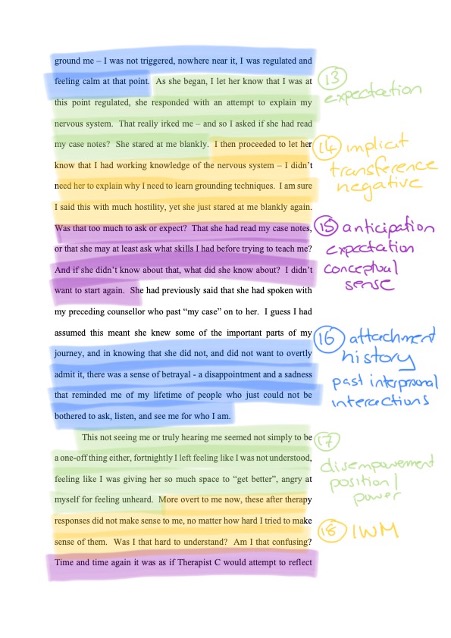

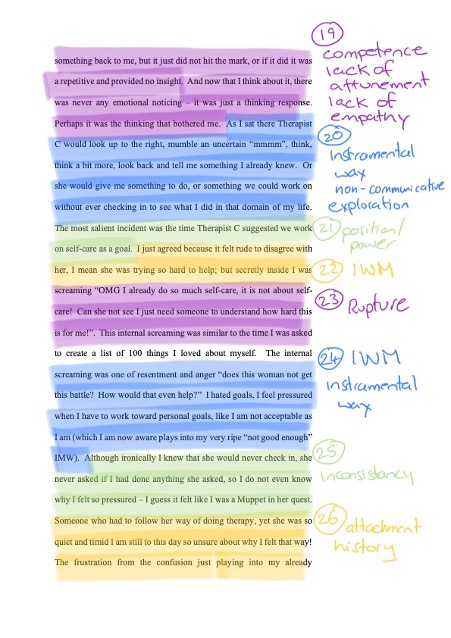

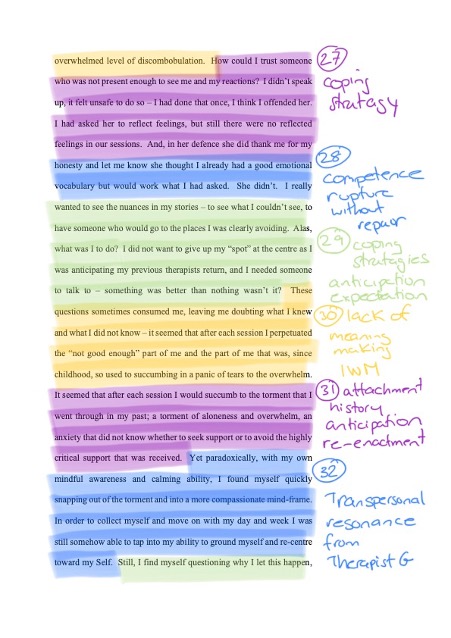

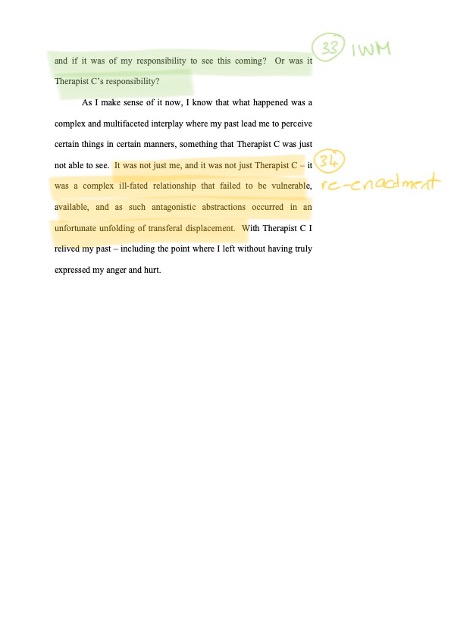

Appendix B