Contents of Article

FROM BROKENNESS TO WHOLENESS HEALING THROUGH FAITH, HOPE, AND LOVE

Identity and the relentless search for self in any paradigm has been a pertinent part of society since Adam and Eve chose to gain the wisdom that broke the sanctity of their child like innocence (Gen 3, NIV; Bible Gateway, n.d.b ¶1). As such, I know I for one, seek understanding in which I can conceptualise what “the self” means. From secular to spiritual philosophies, “the self” has been separated and conceptualized through its various parts for centuries. Though there is a vast array of ideas that both complement and contradict each other, one thing is certain: if my parts remain unknown to me, un- integrated as it were, I live a life in chaos and rigidity (Siegel, 2010, p. xxvi). There is a sense of uneasiness, where the “true self” and the “false self” are at war with one another (Rohr, 2013, pp. 2-3). This sense is a reality for many, including those who seek the assistance of counselling. In order to find their inner harmony, others come knowing that we have first found ours (Siegel, 2010, p. xxvii).

Therefore, when I, as a counsellor, take the time to conceptualise “the self” and its parts, I can come to integration. A sense of harmony through faith, hope, and love that encompasses the soul by the spirit and through the body, allows my “true self” to be the most dominate aspect of who I am, and as such provides a healing space for others (Siegel, 2010, p. xxvii; Marshall, 2001, p. 234; Alexander, 2007, p.22; Rohr, 2013, pp. 184 – 186; 187; 1 John 3, NIV; 1 Cor 13:13, NIV; 1 Thess 5:8, NIV).

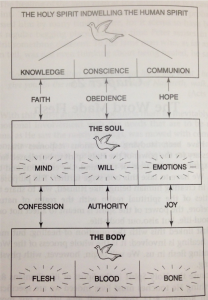

This essay will expand on the abovementioned notions as they relate to Marshall’s (2001) model of spirit, soul, and body (see Appendix One). With a focus on understanding mind, will, and emotions, I hope to offer a self-exploratory theory of what it means to be mindfully present with my “true self” in order to provide space for others to conceptualise their own identity.

UNDERSTANDING WHOLENESS: THE “TRUE SELF”

Understanding “the self” first comes in exploring the definition of what it means to be in one’s “true self”. Personally, I had no concept of my true sense of self until the day I found myself torn in pain, screaming to the heavens in a child-like form “I want to go home”. At the time, I had no idea it was my spirit crying out for my soul to awaken and to return to who I am in Christ: He who is my source and my destiny (Benner, 2012, p.18). Without a true relationship with God (Benner, 2012, p. 83), a sense of identity was unachievable: I was oblivious that I was un-integrated (see “neural integration” Siegel, 2010, p. xii; Siegel, 2012, p. 15; Siegel, 2007, pp. 39-41). In an integrated state the “true self” comprises three sovereign dimensions of spirit, soul, and body, able to distinguish between “me and not me” (Marshall, 2001, p. 234; Abram, 2007, p. 295; Alexander, 2007, p. 19). Further, the “true self” is at peace, willing to meet God in the “depths of [the] soul” (Benner, 2015, p. 101) in order for transformation from the inside out (Bible Gateway, n.d.a, ¶Matthew Henry Commentary; Benner, 2015, p. 101; Alexander, 2007, p. 21).

Yet, how is it that I come to meet God within the depths of my soul? To transform? As abovementioned, Marshall (2001) provides a working model (see Appendix One) which incorporates the notion that we are “thinking, feeling, willing beings” (soul: see also Benner, 2012, pp. 121 -122) in which we relate to both our internal (spirit: see also Benner, 2012, p.22) and external (body: see also Benner, 2012, p. 89) worlds (p. 9). Moreover, where each of these three sovereign dimensions work together in integration to create the “true self” in which faith, hope, and love (1 Cor 13, NIV; Eph 4:4-6, NIV; Col 1:5, NIV; 1 Thess 5:23, NIV; 1 Thess 5:8, NIV) encompass the soul by the spirit and through the body (Marshall, 2011, p. 234; Rohr, 2015, pp. 16-17). However, knowledge of this concept, while holding the basis of transformation or change, is not enough. Quite often it takes an existential crisis of identity in order to accept the invitation to confront the feeling of being “false” (Benner, 2015, p. 51).

Through my own personal experience of disorganised attachments based in trauma and regressed dependence, in which I was unable to become a “person in [my] own right” (Watts, 2009, p. 149), I am able to ascertain the understanding of that which was, and can still be my “false self”. Highly defensive and reactive I sought attachments in seemingly innocent indulgences (Abram, 2007, p. 283; Benner, 2015, p. 75) such as possession, lust, and control. I created a role for myself, acting only in present moments as who others wanted and expected me to be (Alexander, 2007, pp. 121 & 123); suppressing a past filled with unresolved confusion and abandonment and ignoring what I felt, became my identity (Benner, 2015, pp. 72 & 75): there was an extreme “chasm” between my internal and external experiences (Benner, 2015, p.23).

It was only when the walls of this chasm came crashing down with the birth of my daughter, a reflection of pure love, that I realised the “false self” that had been present for so many years, and thus the invitation to acknowledge and heal my broken self came to be. Through continued open reception to the truth in mindful presence (Benner, 2015, pp. 103-104; Siegel, 2010, pp. 1-34), and through internal safety and significance (Siegel, 2012, p. 339; McCann & Pearlman, 1990, p. 158), I came to understand the parts of myself more fully and relationally. Going back to Marshall’s (2001) model (see Appendix One), it is the parts of the soul which open me to who I am in Christ – my “true self” (p. 9) when I am present and allow for receptive healing (Siegel, 2010, pp. 26 & 32).

MIND

The mind is the main frame that links the external (body) to the internal (spirit) in order to create subjective experience (Siegel, 2010, pp. 7-8; Marshall, 2001, p. 25). It regulates and interprets input from six main domains (Marshall, 2001, p. 17): our past (memories); the world (human affairs including: culture, economic systems, technology, politics); the devil (exposure to, and attacks from Satan); the flesh (desire, appetites, needs and drives made for self gratification); the human spirit (connection to conscience and intuitive knowledge); and from God (recognised or unrecognised) (Marshall, 2001, pp. 17- 23). However, without the knowledge of the power of these inputs, which is found in mindful presence, behaviours become misguided and the “false self” becomes most dominant (Marshall, 2001, p. 11; Siegel, 2010, pp. 7-9).

This is never more evident than in my own ailment, where there is a “schism” in my mind (Abram, 2007, p. 308) between the “true self” and “false self”, an un-integrated soul (Masterson, 1981, p. 133; Siegel, 2007, pp. 198-199; Cozolino, 2010, pp. 284-285). When triggered my past dominantly takes over and thrusts me into a mind frame where my spirit and my connection with God are severely severed and exacerbated by the devil. I am thrust into a child-like apparition of myself, consumed with fear, reacting in forms of “brittle, vulnerable, self-depreciative, clinging behaviour, and erratic and irrational outbursts of rage” all based in trauma (Masterson, 1981, p. 30).

EMOTIONS

With emotions in exile, I am unable to trust and am driven into a reactive state where defence mechanisms are protecting the vulnerable and “true self” (Seigel, 2010, p.70; Marshall, 2001, pp. 63 & 64). My own behaviours demonstrating how un-integrated emotions have the ability to distort reality and our subjective experience (Marshall, 2001, pp. 63 & 65). Furthermore, as per my own ailment, implicit memory can trigger emotions that the mind refuses to acknowledge, drawing a wedge between the “false self” and the “true self” into disproportionate sizes and causing a deep wound in need of healing (Marshall, 2001, pp. 65-66). Evidences of wounding can most commonly be seen in relationship, self value, spiritual doubt, despair, and the ability to be present (Marshal, 2001, pp. 66-69; Siegel, 2010, pp. 32-33; Abram, 2007, p. 308). Moreover, sources that inhibit presence and emotional growth, thus the ability to come to our “true self”, stem from trauma based in loss, fear, betrayal, or continued relational miss-attunement (Marshall,2001, p. 67; Siegel, 2010, pp. 42 & 72). Therefore, in order to become more in tune in relationship and indeed with the “true self” one must seek a place of presence where mindfulness leads to integration.

WILL

Further to this, without presence we are unable to truly understand or captivate the meaning of freedom (Marshall, 2001, p. 99; Siegel, 2010, p. 12; Abram, 2007, p. 112), and thus our will, that with which we make choices, has the power to distort or hide “true” internal values. This results in behaviours that break the boundaries of moral law and the authority of God (Marshall, 2001, pp. 101, 104 – 105, 107). As such, the “false self” draws towards existential versions of freedom and authority based in absolutes where obedience is stuck in limiting preconceptions and judgments (Marshall, 2001, p. 101; Siegel, 2010, pp. 13 -14; Siegel, 2012, p. 29).

In my own experience, it has been my spiritual connection with the internal values instilled in me, my conscience, which has drawn my mind from the grasps of the rivalry of God’s law and the law of sin and death (Marshall, 2001, pp. 104-105). The will of the flesh (Marshall, 2001, p. 111) drew me towards an un-integrated soul. Yet deep within me, my connection to the spiritual realms were so strong they allowed my will to acknowledge the “false self” and to seek authority in something grander than an existential existence where I was stuck in preconception and judgment, and where presence was unattainable.

THE WILL TO HEAL

My will was only able to acknowledge the “false self” when I met with a radical encounter with the truth (Benner, 2015, p. 72). It was from this encounter (as abovementioned, as the birth of my daughter) I came to understand the power of the conjunction between my spirit and the Holy Spirit, and as such, I gave in to the internalised values written on my heart, and offered my obedience to the authority of the Cross (Marshall, 2001, pp. 113, 117, & 127). The obedience I offered and still offer today, guides my soul to a state of receptivity where presence makes integration a trait and my “true self” becomes at peace (Siegel, 2010, pp. 31-32).

SEEKING SPIRITUALITY: HEALING THROUGH FAITH, HOPE, AND LOVE

Presence is imperative to healing and in living within our “true self”. That is to say, to truly be aware and receptive and to live in connection with God, we must first offer ourselves in obedience based in love. It is within that, the soul’s will makes choices based on values through the authority of Jesus’ sacrifice (Benner, 2015, p. 13; Marshall, 2001, pp.121-123; Alexander, 2007, p. 73; Bible Gateway, n.d.a, ¶Matthew Henry Commentary; Siegel, 2010, p. 1).

With renewed regulation and interpretation through revealed knowledge received in faith, and spoken through confession (Marshall, 2001, pp. 236 & 239), the desires of the mind are reformed. Through the power of the Cross and the Holy Spirit (Rom 10:8-10 cited in Marshall, 2001, pp. 234 & 236) we may free the limitations of our minds from the input of the six main domains that reside there (Marshall, 2001, p. 11). Moreover, we can bring ourselves closer towards loving-kindness and to receive healed wholeness (Marshall, 2001, p. 239; Seigel, 2010, pp. 83-85; Bible Study Tools, 2014, ¶1-8).

With our limitations free in Christ the entanglements of our emotions are released from the pain of our past (Marshall, 2001, p.75). With hope, emotions can be expressed in the safety of the communion with the Holy Spirit, and with that joy may flow (Marshall, 2001, pp. 86, 234 & 246). The power of the Cross and the Holy Spirit creates understanding to our emotions from a new perspective. This then releases them for their intended purpose of healing (Marshall, 2001, p. 86; Siegel, 2010, p. 72). With a new understanding of our past, we free ourselves from limitations of defence mechanisms and move toward living more in our “true self”.

The abovementioned principals of harmony through faith, hope, and love that encompass the soul by the spirit and through the body are just the beginning of the journey. That is to say, the “true self” cannot be fully realised until understanding and integration through continued presence takes place in truth and through truth (Siegel, 2010, p. 91). We must actively seek presence to allow the work of the Cross and the Holy Spirit to integrate our souls, bringing us into our “true self”.

PRACTICAL CHANGE

With the concept of the “true self” in place alongside the notions of what it means to be healed: living in the self whom resides in Christ (John 15, NIV, Rohr, 2013, p. 16) and the “only self that will support authenticity… and provide eternal identity…” (Benner, 2015, p.17), we can knowingly move towards connection, security, and of truly being seen (Siegel, 2010, p. xx). Though it may be a long and slow journey in acknowledging and understanding the dark sides of ourselves (Alexander, 2007, pp. 121 – 122), when we actively seek presence, healing is differentiated, sanctified, and integrated within our lives and relationships (Siegel, 2010, p. xii; Alexander, 2007, p. 125; Collins, 2007, p. 66).

Through my own journey, I have come to understand that there is power in mindfulness through cultivating true presence. My ability to be “conscientious, creative, and contemplative” (Siegel, 2010, p. xxv) comes from focusing my mind “… in specific ways to develop a more rigorous from of present moment awareness that can directly alleviate suffering…” (Siegel, 2007, p. 9; see Mind Your Brain, Inc, 2010, ¶1-5, Wheel of Awareness Practice for “specific ways”).

In saying this there is no better way to portray the concept of healing and freedom as conceptualised in the abovementioned notions, than to come to conclusion through bringing my own journey. My hope is to demonstrate the power of the Cross and the Holy Spirit, as well as integration of mind and emotions, is led by a moral will that intuitively “knows” (Rohr, 2007, p.52; Benner, 2015, pp. 38-40; Siegel, 2007, p. 334; Marshall, 2001, p. 234).

BROKEN BY BETRAYAL; RESTORED IN FAITH, HOPE, AND LOVE

Those who have experienced trauma of any kind understand my plight. There is a desperate search of self, and a desperate need to resolve that which inflicted me and made my mind incoherent for so many years (Siegel, 2010, pp. 189-190; Marshall, 2007, p.86).

It is now, some four years after I first began my journey towards my “true self”, that I have come to somewhat understand what it meant when I was screaming to the heavens to “go home”. I have now come to understand that for the most part of my life I was living in falsity, unable to reconcile or integrate memories, emotions, values, truth, nor what I knew intuitively: it was only when I came to a breaking point that I was able to make the choice to come to truth (Siegel, 2010, p. 91).

Through making a choice, through continually making choices each and every day to be humble and to walk alongside Christ, I am able to acknowledge my fallibility and to seek that which opens me to towards my “true self”.

Although I have, and do, practice a variety of tools and techniques (such as CBT, IPT, EFT, Yoga, DBT, client-centred, and the like) there has been nothing more effective than bringing my wounded child-self filled with implicit pain memories to the foot of the Cross within a mindful state of presence (Siegel, 2010, pp. 1-33; 194-196). It is there, within my safe space, I vision the Cross and allow the Holy Spirit to wash over me. With the knowledge that I am free in the new covenant (Marshall, 2001, pp. 121-131) I am able to “be open not only to how things are, but to how they change moment to moment” (Siegel, 2010, p. 197). This allows me to honour, understand, and to be obedient toward the authority of God and to acknowledge the values I reside in and the forgiveness I must seek for that which torments me.

It is within this that I am able to further recognise the truth, and to mindfully, through written prose, spoken confession (Marshall, 2001, pp. 234-239), and with an open heart to hear, communicate with God, and to allow new thought patterns to emerge. With practice I have come to understand this process as that which instills the new thought patterns within my complete being (Siegel, 2010, pp. 259-260; see also pp. 253-260).

Furthermore, healing has not come without a sense of acceptance, security, guidance, and love from a deep connection within community; I have found a sense of compassionate understanding and relational value within the presence of God and others. And while my own healing has been a development of mindful, spiritual practice over years, I come to acknowledge that healing in others, particularly in the Christ-centered, Bible-based context, comes from my own ability to recognise who I am in Christ. That is, incorporating a sense of faith, hope, and love that encompasses the soul by the spirit and through the body, allows my “true self” to be the most dominate aspect of who I am, and as such provides a healing space for others to find freedom in their “true self”.

References

Abram, J. (2007). The language of Winnicott: A dictionary of Winnicott’s use of words(2nd ed.). London, Great Britan: Karnac Books.

Alexander, I. (2007). Dancing with God: Transformation through relationship. London, Great Britan: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

Benner, D. G. (2012). Spirituality and the awakening self: The sacred journey of transformation. Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press.

Benner, D. G. (2015). The gift ofbeing yourself: The sacred call to self-discovery. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

Bible Gateway. (n.d.). Gen 3:7–11 – Reformation Study Bible – Bible Gateway. Retrieved from https://www.biblegateway.com/resources/reformation-study- bible/Gen.3.7-Gen.3.11

Bible Study Tools. (2014). The humility of Jesus. Retrieved from

http://www .biblestudytools.com/classics/murray-humility/humility-in-the-life-of- jesus.html

Collins, G. R. (2007). Christian counseling: A comprehensive guide. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson.

Cozolino, L. J. (2010). The neuroscience of psychotherapy: Healing the social brain(2nd ed.). New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co.

McCann, L., & Pearlman, L. (1990). Psychological trauma and the adult survivor: Theory, therapy, and transformation. London, Great Britain: Brunner-Routledg.

Marshall, T. (2001). Living in the freedom of the spirit. Lancaster, England: Sovereign World. Masterson, J. F. (1981). The narcissistic and borderline disorders: An integrated developmental approach. New York, NY: Brunner-Routledge.

Mind Your Brain, Inc. (2010). Wheel of Awareness. Retrieved from www .drdansiegel.com/resources/wheel_of_awareness/

Rohr, R. (2013). Immortal diamond: The search for our true self. London, Great Britan: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

Siegel, D. J. (2007). The mindful brain: Reflection and attunement in the cultivation of well-being. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co.

Siegel, D. J. (2010). The mindful therapist: A clinician’s guide to mindsight and neural integration. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co.

Siegel, D. J. (2012). Mindsight: Change your brain and your life. Brunswick, Australia: Scribe Publications.

Watts, J. (2009). Donald Wincott. In J. Watts, K. Cockcroft, & N.

Duncan (Eds.),Developmental psychology (2nd ed., pp. 138-152). Cape Town, South Africa: UCT Press.

Appendix One