Contents of Article

MIND BODY CONNECTION

& the Functional Fundamentals of Humanity

Nothing can cure the soul but the senses, just as nothing can cure the senses but the soul.

Oscar Wilde

Fundamental Constitution of Self

It is important to ground psychotherapies on a knowledge of affective processes and thereby to understand how to most effectively recruit beneficial cognitive perspectives. Panksepp and Biven, 2012

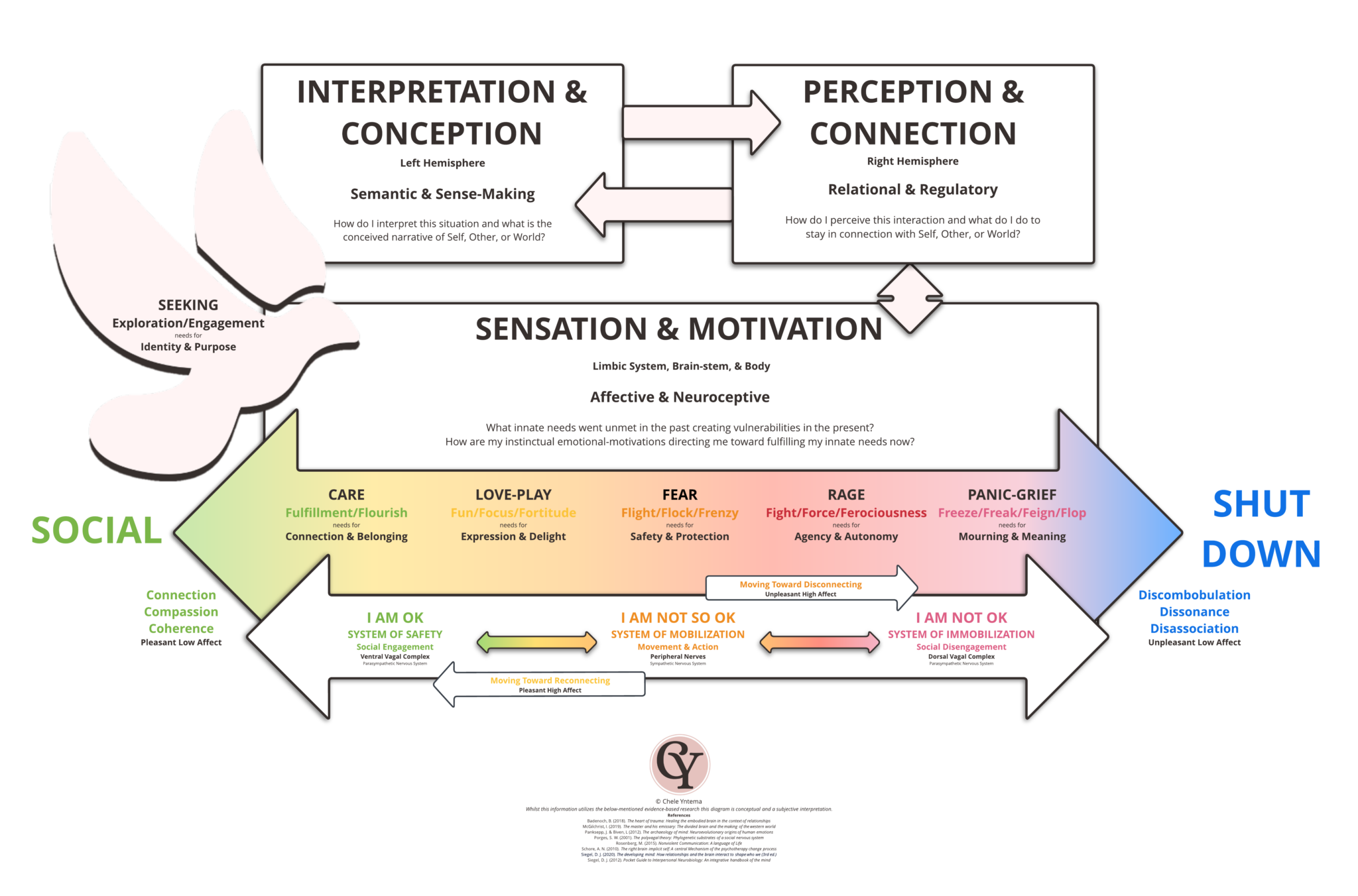

As we become more aware of what it means to be human and the fundamental nature of experiencing, it becomes essential to also acknowledge and appreciate some of the neurobiological aspects of our individual being in the world. This underlying understanding incorporates the physiological, psychological, and relational characteristics of the body and mind as they mediate the phenomenological experiencing of our being (Panksepp and Biven, 2012; Siegel, 2012). When we acknowledge these characteristics, we might begin to envision how our experiencing could be conceptualised through three affectedly and effectually interacting regions of neurobiological based processing (Panksepp and Biven, 2012). Such interactive regions can be articulated as:

- Sensation & Motivation (the embodied, affective, and neuroceptive energy emerging within primary processes)

- Perception & Connection (the receptive, relational, and regulatory energy and information emerging within secondary processes)

- Interpretation & Conception (the discerning, semantic, and sense-making energy and information emerging within tertiary processes)

Moreover, when we differentiate and enumerate these regions, we come to see how the underlying interacting systems and structures relate to and regulate the ever-emergent flow of energy and information within and between Self, Other, and World (Leiper, 2013; Siegel, 2012).

To clarify, when differentiate and enumerate some of the neurobiological aspects of our individual being in the world, we come to understand that there are certain neural processes, both inherent and adaptive, that underscore how we sense, perceive, interpret, then react or respond to situational stimuli in the manner that we do (internally and externally; interpersonally and intrapersonally) (Cozolino, 2002; Fosha, 2005; Panksepp and Biven, 2012; Siegel, 2012). And, most vitally, it is in this understanding that Self, Other, and World awareness opens opportunities for moment-to-moment attuned reciprocity to the humanness within and between. To mindfully respond to, rather than to react to, situational stimuli (internally and externally; interpersonally and intrapersonally). This in turn broadens and builds the Self’s capacity to meet challenges with rigor, which further ignites the Self’s innate capacity to move toward potentiality with purpose and meaning.

Sensation & Motivation

Based on the work of Panksepp and Biven (2012) the notion of “sensation”, as I am defining it here, can be seen as an inherent and epigenetically formed instinctual asset of our biopsychosocial nature that enables the Self to interact with Others and the World in distinct emotional-motivational manners. Such is an arrangement of seven neurological structures that each hold a universal knowing of our innate needs for survival – individually, familiarly, and phylogenetically. And, whilst each structure directs unique forms of life-force, they each have certain properties in common. These commonalities include:

- That they emerge essentially objectless, initially unconditioned response tendencies to unconditioned stimulus that become connected to the world through learning and development (Panksepp and Biven, 2012, pp. 134; 176).

- Although each structure is characterised by specific affect, they are interactional in open, non-linear, chaos capable manners – each structure is fractalated and complex (Panksepp and Biven, 2012, p.190; Siegel, 2012, p. AI:17).

- The primary-process structures are among our most essential value-coding mechanisms, each distinctly valenced motivating us toward universal needs (Panksepp and Biven, 2012).

- Structures can be classified as pleasant or unpleasant, high or low, social or defensive (Panksepp and Biven, 2012; Porges, 2001).

- These structures yield evolutionary/generational experiences that guide the expression of secondary and tertiary processes, creating perceivable and interpretable patterns between past, present, and future (Badenoch, 2018, p. 139; Panksepp and Biven, 2012, p. 328).

- Primal Affects are prelinguistic experiences – experiences common to all mammals (Panksepp and Biven, 2012, p.79)

Additionally, Panksepp (2010) defines these structures as basic emotional networks that can be defined by six principles:

- They generate characteristic behavioural-instinctual action patterns

- They are initially activated by a limited set of unconditional stimuli

- The resulting arousals outlast precipitating circumstances

- Emotional arousals gate/regulate various sensory inputs to the brain

- They control learning and help program higher brain cognitive activities

- With maturation, higher brain mechanisms come to regulate emotional arousals (p. 534)

With this in mind, I acknowledge that these seven primary-process affective structures align in accordance with Porges (2001) notion that the autonomic nervous system is a phylogenetically determined hierarchy of functional complexes that can be organised into three sequential systems including:

- Social Engagement and the System of Safety, or the Ventral Vagal Complex (VVC).

- Movement and Action and the System of Mobilisation, or the Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS).

- Social Disengagement and the System of Immobilisation, or the Dorsal Vagal Complex (DVC).

This hierarchical organisation of evolution and dissolution is one whereby the newer VVC complexes have the capacity to inhibit the older SNS and DVC complexes (Porges & Phillips, 2015). Indeed, our social engagement systems are designed to connect (with Self, Other, and World) and hold the capacity to down-regulate mobilisation bringing about calm (with Self and/or Other), just as movement and action and our systems of mobilisation are designed to keep us from social disengagement and immobilisation (Porges & Phillips, 2015). Whilst this hierarchy is not specifically articulated by Panksepp and Biven (2012), my understanding of their research and my knowledge of responses to environmental challenges from a therapeutic perspective has led me to conceptualise “sensation” as inclusive of Panksepp & Biven’s (2012) affective structures as they rest within the bounds of Porge’s (2001) hierarchical organisation of evolution and dissolution.

Notably, I have found it helpful to conceptualise that our primary affective structures are intrinsically linked to the systems of safety, danger, and life-threat which in turn are designed to respond reciprocally to other mammalian systems (Panksepp and Biven, 2012; Porges & Phillips, 2015). To be specific, our primary-process structures are comprised of a CARE Circuit, a PLAY LOVE Circuit, a FEAR Circuit, a RAGE Circuit, and a PANIC GRIEF Circuit that are evermore linked to an overarching SEEKING Circuit. It is important to highlight here that these systems are not all-or-none stand-alone responses. Indeed, these systems are designed to include transitional blends between the boundaries of engagement, action, and disengagement – these primary-process structures of affect exhibit graduations of control which are determined by feedback loops and higher mental processes (i.e., secondary and tertiary; Porges, 2001).

Whilst seemingly complex, it is with a nuanced understanding of this innate, interacting physiology that we become more able to attune to the subtle aspects of sensation (in Self and of Other), linking them to our perceptions and interpretations (of Self, Other, and World), and to respond to such with connected awareness, intention, and significance.

These systems shall therefore be delineated herein.

The SEEKING Circuit

The overarching structure of SEEKING is beyond the bounds of the divisible systems of sequential activation (i.e., VCC, SNS, DVC) as it is the structure by which all other emotional-motivational structures are energised. Fundamentally SEEKING is an instinctual mammalian asset that motivates one to move out into the world in engagement and exploration. SEEKING is innately sensed by Self as pleasant and can counteract some of the unpleasant arousals of the other emotional-motivational structures. This occurs as this structure provokes a sense of eager anticipation, enthused euphoria, and significantly, the sense that one has the capacity as an effective agent of change. SEEKING is the structure of expectancy that lies at the heart of all “intentions-in-actions”. Indeed, whilst SEEKING can be a “goad without a goal”, when activated with other primary-processes and when connected with higher mental processes SEEKING becomes the hope for, and the desire to seek, find, and acquire resources needed for survival (universal needs). Further, whilst this structure is designed to respond to exteroceptive, proprioceptive, and interoceptive indications of homeostatic imbalance (including social needs), it is also highly prone to respond to greed. Meaning, even when needs are satisfied one can be drawn to enticing excitatory stimuli – SEEKING can easily become an overactive urge to indulge without forethought to the effects of such indulgence. As such, SEEKING can be understood as on an appetitive continuum rather than a consummatory compulsion – it is not the reward that specifically arouses or drives the urge, rather it is the uniquely euphoric embodied sensation that occurs from one’s capacity to move out into the world as an actively engaged agent, as opposed to simply an insentient object or a passive bystander. Thus, SEEKING can be seen as wide-ranging states of engagement that propel one to take notice of, to examine, and to learn from the novel stimuli that might assist one in making sense of the world and the resources it has to offer.

As the motivational structure that underscores all other emotional-motivational structures, innate SEEKING activity (unconditioned seeking, finding, and acquiring of resources) is fuelled heavily by the neurochemical dopamine and, with the excitatory neurochemical glutamate, is also a structure of appetitive learning and memory. Importantly, whilst each of the affective structures emerges essentially objectless it is through learning and development that unconditioned stimuli and responses become associated. These associations create and enhance the affective foundations of memory – inherently we begin to pay attention to that which is pleasant (“rewarding”) or unpleasant (“punishing”), moving out into the world with the capacity to anticipate and survive future events by using past experiences as a compass. Thus, SEEKING can not only be seen as the catalyst of a sustained curiosity that seeks, finds, and acquires, but also the catalyst of adaptation whereby attention to extraneous stimuli begins to evolve in evermore patterned ways. Moreover, it is this patterning in which insight and an ongoing hope-faith link produces a sense of Self, Other, and World. With the innate appetitive/excitatory tendency of the SEEKING structure we are impelled toward linking primary-process affects and their propensities to objects, events, or environments, providing development, learning, and thus memory of how to be an effective agent in the world. Thus, SEEKING can be seen as the structure that energises biopsychosocial development, and more specifically, the overarching human search for purpose and identity.

This is the primary-process by which all other primary-processes become linked to perception and interpretation – without an initial emotional-motivation such as SEEKING, survival becomes reticent of reciprocating faith, hope, and love (See Panksepp and Biven, 2012, pp. 48-95; pp. 176-203)

The CARE Circuit

“The roots of human empathy reach deep into the ancient circuits that engender caring feelings in all mammals, where we identify our own well-being and the well-being of others… It has long been known that the most effective therapy occurs when therapist know how to approach clients with unconditional acceptance, empathetic sensitivity, and a full concern for their emotional lives – in a word, effective therapists share their ability for CARE…” (Panksepp and Biven, 2012, pp. 284, 310).

The structure of CARE falls within the bounds of the VVC and can generally be classified as a socially motivated affect with a low arousal; CARE is innately sensed by Self as pleasant. CARE is the first system of social engagement and a system of nurturing safety. Alongside PLAY and GRIEF, CARE is one of the three structures that supports non-sexual social bonding and attachment. Indeed, whereas GRIEF inhibits PLAY, CARE is the primordial nurturing urge that responds to and moderates GRIEF. This in turn enables mammalian connection and belonging. While CARE is primarily epitomised by maternal devotion, it is also a nurturing source of intimate engagement and devoted love; it is that which provides a profound sense of fulfilment and flourishing.

As a reciprocating structure of Self, CARE is intrinsically linked to the Other through the exteroceptive senses, specifically sight, sound, touch. Each sense with the capacity to facilitate accepting, positively valenced pro-social interactions and fuel a richness in neurochemical connectivity through oxytocin and endogenous opioids. Oxytocin is known to promote the higher mental processes of trust, confidence, empathy, compassion, altruism, and in conjunction with endogenous opioids, an overall sense of calm coherence. Such a sense of calm ties back to the urge of maternal devotion, the affective propensity toward nurturing meaningful tenderness, and the urge to stay socially connected. (See Panksepp and Biven, 2012, pp. 283-310)

The LOVE-PLAY Circuit

The structure of PLAY* falls within and between the bounds of the VVC and the SNS such that activation entails movement with safety. However, PLAY can easily shift to movement with danger when the desired or predicted bounds between players are broken. Thus, PLAY can generally be classified as a socially motivated affect with high arousal, and is innately sensed by Self as pleasant. PLAY is the second system of social engagement as well as a system of movement and action; accordingly, making PLAY a system of social learning and development – both physiologically and psychologically. Such social development emerges from the nascent attachment urges of invitation and exchange, aggression and placability, competition and collaboration, as well as maternal and paternal propensities. While PLAY is primarily symbolised in childhood by physically engaged interactional dynamics (such as rough and tumble play), as individuals mature such dynamics tend to exhibit more psychological dynamics (such as friendly teasing or joking). Such is an interactional dynamic that depends on reciprocity, equality, and equanimity – particularly a sharing of dominance or submission behaviours.

As a reciprocating structure of Self that enables mammalian needs for both expression and delight, PLAY is an experience-expectant neurobiological process that prepares individuals for future challenges and opportunities – PLAY is intrinsically linked to the Other and, in childhood, may guide a maturing social intelligence that allows an individual to identify Others with whom they can create cooperative relationships and to know who they should avoid. Thus, PLAY assists to develop social-emotional capacities which stitch “individuals into a stratified social fabric that will be the staging ground for the rest of their lives” (Panksepp and Biven, 2012, p. 355). Moreover, PLAY may fuel a richness in endogenous opioids, endogenous cannabinoids, and dopamine (due to its innate linkage to the SEEKing structure), which in turn mediates a sense of fortitude, focus, and fun.

PLAY can be seen as both a robust and fragile structure: although it is robust in its capacity to promote higher brain growth related to expressing creativity, appreciation, gratitude, joy, intimate love, and a zest for life, PLAY is fragile in its association to environmental stimuli that can evoke feelings correlated with the structures of FEAR, RAGE, and PANIC/GRIEF. PLAY requires social warmth, support, and affiliation (CARE) in order for the Self to engage in the pro-social activities that facilitate the maturation of social sensitivity, determination, reliance, esteem, satisfaction, and the overall sense of purposeful competence in life. Such a sense of competence ties back to the urge to interact and attach, the affective propensity toward reciprocating equality and equanimity, and the urge for dynamic connection. (See Panksepp and Biven, 2012, pp. 203-282)

*Panksepp and Biven, 2012 have identified and enumerated a structure of PLAY and a structure of LUST. I here delineate the structure of PLAY and negate the structure of LUST due to the intricacies in the male/female distinctions, the relationship to generally known aspects of sexual development and the associated urges, as well as the complexity associated with the notions of sexuality, gender, identity and the neurochemical complexities this structure entails. Within my delineation of PLAY however, I incorporate the aspects of LUST that could potentially be more primitive social aspects of PLAY. For example, qualities of social relationships and the nature of dominance, will determination, and urges to either approach, avoid, or aggress. (See Panksepp and Biven, 2012, pp. 351-388)

The FEAR Circuit

The structure of FEAR falls within the bounds of the SNS and can generally be classified as a defence motivated affect with a high arousal; FEAR is innately sensed by Self as unpleasant. FEAR is the first system of danger and a system of protective mobilisation. Alongside RAGE, FEAR is one of the two structures that are highly anticipatory and as such can easily become sensitised by a lack of attachment security and stability. Correspondingly, while FEAR and RAGE are two distinct structures, they are inherently reactive to each other through their anatomical and chemical entwinement – both structures born to work in tandem. Such reactivity is one whereby the ascendency of one structure over the other depends on the form of danger an individual is faced with.

FEAR is a reciprocating structure of Self that that is intrinsically linked to the Other through the urge to counter predation (injury or premature death) – this is the mammalian capacity that enables safety and protection of Self and Other. Indeed, FEAR can act as a social brake, inhibiting interactions of curious exploration until safety is restored.

Although FEAR is fundamentally an unconditioned free-floating anxiety that responds only to phylogenetically determined stimuli (e.g., pain is a universal provocation of this structure; lack of touch is a human provocation), FEAR quickly becomes conditioned by experiences of situational danger or pain. Accordingly, FEAR is the predominate primary-process affect highly connected to the amygdalae. These amygdalae connections generalise from past learning making associations to inner and outer sensory based conditions. However, without spaciotemporal data this generalisation creates contextless embodied memories (perception) that link with higher cortical processes (interpretation) which then generate anticipatory defences based in those learned conditions. Indeed, while the amygdalae are responsible for emotionally salient learning and the expediently powerful mobilisation of the SNS, the innate creation of affective anxiety and resulting action is wholly dependent on deeper connections within FEAR structures. Moreover, it is essential to reiterate the anticipatory nature of this structure and thus the propensity for these connections to be sensitive to attachment-based learning. Meaning, should the amygdalae be continually conditioned by ongoing experiences of pain or danger (e.g., abuse/neglect) associations become hyperactive. Consequently, connections and associations can fragment creating a disorganised sense of free-floating worry that is disconnected from an accurate perception or interpretation of the environment.

As can be deduced, FEAR is the emotional-motivational affect behind the more commonly known stress response (the CRF-ACTH-Cortisol system). Such response is that which involves a cascade of neurochemical activity through the sympathetic-adrenomedullary system – including the endogenous catecholamines epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline) – as well as through the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenalcortical system – which includes corticotropin-releasing hormone and adrenocorticotropic hormone. This cascade of neurochemical activity in turn signals the creation of cortisol which down regulates the systems not crucial for moments of Flight, Flock, or Frenzy (reproduction, immunity, digestion and growth). Each of these elements preparing the body for mobilisation through distinct physiological changes. Correspondingly these physiological changes highlight that the underlying structure of FEAR and it’s affective propensity to sense of anticipatory apprehension (or anxiety) innately ties back to the urge to survive threat. (See Panksepp and Biven, 2012, pp. 175-202)

The RAGE Circuit

The structure of RAGE falls within the bounds of the SNS and can generally be classified as a defence motivated affect with high arousal; RAGE is innately sensed by Self as unpleasant. RAGE is the second system of danger and, alongside FEAR, a system of protective mobilisation. Yet, whereas FEAR structures are more vigilant of safety, RAGE structures react to the thwarted mammalian needs for agency and autonomy. Correspondingly, RAGE is epitomised by ferocious aggression and the motivation to “bring others in line, rapidly, with one’s implicit (evolutionary) desires” (Panksepp and Biven, 2012, p. 147); this is particularly evident when resources are scarce or there is an inhibited capacity to counter predation through FEAR based actions. As such, FEAR can arouse RAGE and RAGE can arouse FEAR which, rather than promoting co-operation in needs acquisition, may paradoxically serve to perpetuate the physiological stress response and a reciprocation of FEAR and RAGE within and between Self and Other; thus, conditions of danger heighten and perpetuate without resolve.

Although RAGE is born objectless and fundamentally responds, as FEAR does, to phylogenetically determined stimuli (e.g., physical irritation is a universal provocation of this structure: a lack of homeostatic needs such as hunger), RAGE becomes connected with higher mental processes through ongoing sociocultural development. Such development includes connecting secondary and tertiary processes to ruminating feelings of anger and the learned affinity to associate the affect propensity with a transgression or transgressor through blame, criticism, manipulation, resentment, hatred, jealousy, or the like. However, while these associations seem to quell the need for agency and autonomy alongside safety and protection, as aforementioned, the internal and external reciprocity between the structures of RAGE and FEAR may paradoxically prolong the physiological stress response and thus conditions of danger.

Therefore, RAGE requires warm recognition, understanding, and support (CARE) in order for the Self to engage in pro-social communications that facilitate the maturation of emotional wisdom and the higher mental processes that regulate the reciprocity between of RAGE and FEAR structures. These are communications within and between Self and Other that recognise the fierce urge to aggress through dominance and control, that acknowledges the perception or interpretation of the Other as adversary, and that utilises the affective structures of CARE and PLAY to resolve the conditions of danger. With this in mind, it cannot be negated that ultimately the innate sense of RAGE ties back to the protective urge to survive threat through Fight, Force, or Ferociousness and, without CARE, is not easily tamed. (See Panksepp and Biven, 2012, pp. 145-176)

The PANIC-GRIEF Circuit

The structure of GREIF* falls within the bounds of the DVC such that activation quickly progresses from movement with distress to inert arrest. This is an enigmatic form of establishing safety through social disengagement. Thus, GRIEF can generally be classified as a socially motivated affect with low arousal and is innately sensed by Self as unpleasant. Often emanating from a resigned SNS system, yet not solely dependent on preceding or overt FEAR/RAGE activation, GRIEF is the only system of life-threat (physical, psychological, real, or perceived) and is a system of protective immobilisation. Interestingly, as responsive to life-threat GRIEF holds two paradoxical facets of arousal. When safety and protection, as well as agency and autonomy, have in some way been thwarted, there is an initial phase of PANICked distress that motivates reconnection to CARE, and when such terror has exhausted all alternative resources, GRIEF’s urge is to regress into a behaviourally inhibited despair or despondency in order to conserve energy. This can bring about a severe sense of isolation or an embodied sense of alarmed aloneness that can be slow to resolve. Moreover, GRIEF can be understood to be an affect that, whilst being intrinsically linked to FEAR through emotionally salient stimuli and the neurochemical activity of the stress-response, has secondary effects that occur from exhausted synaptic chemical resources or imbalances of the CRF-ACTH-Cortisol system. Such imbalances can result in reduced levels of neural growth factors and increases in inflammatory processes within the body and brain. Importantly, as GRIEF is designed to protect and reconnect helpless mammalians through the mediation of Freeze, Freak, Feign, or Flop reactions, imbalances and the secondary effects can be minimised and reversed through connection and belonging. That is, GRIEF is the mammalian capacity that, with re-connection to CARE (in Self or Other), enables meaning and mourning which in turn activates the neurochemical activity associated with the CARE structure (i.e., Oxytocin and endogenous opioids). Thus, GREIF is unexpectedly an affect of discomfort and insecurity as well as an affect of release, comfort, and security.

As a reciprocating structure of Self that enables the mammalian need of attachment in times of distress, GRIEF, like PLAY, is an experience-expectant neurobiological process that prepares individuals for future challenges and opportunities. As intrinsically linked to the Other GRIEF may guide a maturing capacity to identify meaning in loss and the ability to trust that the Self is capable of surviving and reviving from extreme pain. Interestingly, the GRIEF structure evolved from primordial pain structures thus intrinsically linking separation from CARE-givers, or as the brain matures many other forms of social-separation, to the affective intensity of rejection and abandonment. Indeed, such development reveals the intersection between physical and psychological distress and the profound nature of our desire to create lasting social bonds. Moreover, such an intersection may fundamentally highlight the attachment urge to be part of meaningful socio-cultural systems and the influence of socio-cultural “norms” on the developing mind of a child – to be shamed, excluded, ridiculed, or the like, is an intensely disconcerting, distressing experience that can epigenetically alter affective temperament proclivities and the perception of painful stimuli. Thus, GRIEF is ultimately a structure that supports a level of bonding and attachment to CAREing Others that, if matured in healthy environments, enables the urge to re-connect inter- and intra-personally so as to process all emotionally salient stimuli in the service of future distress or loss. (See Panksepp and Biven, 2012, pp. 311-350)

*Panksepp and Biven, 2012 “originally called the primal emotion that promotes infant bonding to mothers as the PANIC system. This unusual label was used to highlight the fact that when most young mammals are separated from their primary caregiver, the feelings engendered may resemble a “panic attack”… [They] still think this is a good label for the primal affect generated by the “separation distress” system. However, in older animals and humans, with well established affection bonds, social loss can activate a fuller spectrum of distressing affects that are more easily described as sadness or grief and loss” (pp 284-285).

As has hopefully been illustrated through the enumeration of the seven primary-process affectual structures we each have, embedded in our evolutionary DNA, interacting and reciprocating neurobiological structures that hold intrinsic instinctual motivations or “intentions-in-actions” toward satisfying our universal needs for connection and belonging, harmony and delight, safety and protection, freedom and autonomy, as well as meaning and mourning through seeking, finding, and acquiring the resources most meaningful for survival (Badenoch, 2018; Panksepp & Biven, 2012; Rosenberg, 2015).

Perception & Connection

Based in the knowledge derived from Interpersonal Neurobiology, Attachment Theory, as well as hemispheric asymmetry and orientation, the notion of “perception”, as I am defining it here, can be seen as an adaptive asset of our biopsychosocial nature that implicitly attunes to patterns within the flow of energy and information provided by the body and midbrain through affect (sensation and the peripheral nervous system – inclusive of the somatic and visceral senses). This integral attunement opens our capacity to synthesizes implicit aspects of the present moment with past experiences bearing affective value. Such is often without conscious awareness yet impacts internal meaning and our instinct to establish a felt sense of dynamic equilibrium (primarily safety through the social engagement system). This is the capacity of the mind-body that, when integrated, enables the Self to regulate and relate with Other(s) and the World.

Such may be a structure and a function predominant (albeit not exclusively) of the right hemisphere that opens implicit attention to that which is universal and contextual whilst unifying embodied awareness with flexibility and possibility (McGilchrist, 2009); this is a connected knowingness that rapidly complexifies indirect syntheses of meaning as it relates to novel experience and an ever-emerging future (McGilchrist, 2009). As such, perception orientates the Self toward the moment-to-moment flow of unfolding energy and information, specifically those that exist within and between Self, Other(s), and World (Badenoch, 2018; Siegel, 2012).

Perception as a right hemispheric function is one wherein subjective relational meaning is derived and implicitly memorised – a process of affect embodiment that, whilst underlies the capacity for perceptual links between words, holds no expression of complex syntax, syllogistic reasoning, nor the ability to abstract notions from the present moment (Badenoch, 2018; McGilchrist, 2009; Schore, 2010; Siegel, 2012). Indeed, what I am here attributing to perception are the neurobiological structures that non-consciously beings to organise the Self’s interactions with the primary Other for future implicit somatic attributional meaning of Self in relationship with Others and the World (McGilchrist, 2009; Shaver & Mikulincer, 2008).

This is a structural growth process that potentially begins in utero and becomes dominant from birth up until the second year of life when hippocampal and left hemispheric structures begin to take form producing grounded conceptions of experience (Badenoch, 2018; McGilchrist, 2009; Schore, 2010; Siegel, 2012).

With this in mind, one can begin to fathom this structure-function connexion as that which adaptively allows the Self to visuospatially perceive emotionally salient interpersonal interactions (safety, danger, or life threat) as they pertain to seeking and finding availability and responsiveness (safe haven), proximity and support (secure base) (McGilchrist, 2009; Shaver & Mikulincer, 2008; Teyber & Teyber, 2017).

To this end I finally define and enumerate perception as a notable faculty that, as it represents an implicit regulatory means to meet the valenced motivations of our affect, is an embedded form of sensorimotor knowledge which can serve defensive and self-protective functions (Pietromonaco & Barrett, 2000; Shaver & Mikulincer, 2008). Indeed, if in the early stages of life the affective cries of the Self are met with forms of unavailability or unresponsiveness, indulgence or control, abuse or neglect, the inter- and intra- personal characteristics of the Self begin to emerge in disintegrated and dysregulated manners – the Self becomes reliant on protective forms of regulation (Teyber & Teyber, 2017).

That is, the right hemisphere begins to develop and rely upon activating or deactivating nonverbal expressions of neediness and actions aimed at re-establishing safety in connection (Shaver & Mikulincer, 2008).

Conversely, if in the early stages of life the Self’s affective cries are met with forms of availability and responsiveness, proximity and support, the Self becomes aware that one can trust an Other for a felt sense of security that holds a balance between establishing intimacy and maintaining independence; this is a rich base for resilience and the capacity of the Self to access internal regulatory resources required for flexibly fulfilling the Self’s universal needs throughout the lifespan (Panksepp & Biven, 2012; Pietromonaco & Barrett, 2000; Shaver & Mikulincer, 2008). That is, throughout the lifespan the Self can continue to cultivate and engage in meaningful interactions that perpetuate a sense of worth and social significance (Pietromonaco & Barrett, 2000; Shaver & Mikulincer, 2008).

Interpretation & Conception

Based in the knowledge derived from Interpersonal Neurobiology, Attachment Theory, as well as hemispheric asymmetry and orientation, the notion of “interpretation”, as I am defining it here, can be seen an adaptive asset of our biopsychosocial nature that, with more explicitness (though paradoxically often non-consciously), conceives and transforms the perceived patterns of energy and information flow retrieved from the right hemisphere. This conception and transformation may alter, reorganise, and interconnect perceptions with discernible symbolic value and emergent dichroitic meaning; such may be a level of processing by which “selecting, sorting, segmenting, shifting, grouping, categorizing, comparing, contrasting, coalescing, transfiguring, labelling, associating, and recombining” occurs (Siegel, 2012). This is the capacity of the mind-body that, when integrated, feeds this information back to the right hemisphere which in turn enables the Self to discerningly and coherently make sense of its Self as it exists alongside Other(s) in the World (McGilchrist, 2009; Panksepp & Biven, 2012; Siegel, 2012).

As can be alluded, such may be a structure and a function predominant (albeit not exclusively) of the left hemisphere that focusses attention whilst abstracting an understanding of what has been “perceived” as it relates to practice, predictability, and prioritising what is already known and expected (McGilchrist, 2009); this is an understanding that takes the past and distillates it in relation to the immediate future (McGilchrist, 2009).

Interpretation as a left hemispheric function is one wherein locally organised representations of energy and information are explicitly conceptualised and encoded – this is a function by which experience is clarified and shaped with detail and language (McGilchrist, 2009). Moreso, interpretation is a process of synthesis that expresses these representations in analytical, directive, declarative, logical, lineal, literal, segregated, rational, and utilitarian manners (McGilchrist, 2009; Siegel, 2012).

This is a seemingly objective evaluation that orientates the Self toward the known aspects of the World that assists in creating a sense of stability through narrative (Siegel, 2012). Indeed, what I am here attributing to interpretation are the neurobiological structures that reinforce the uniquely human capacity for a conscious coordination of knowledge and memory – factually and autobiographically (Siegel, 2012). This is a process derived from our fundamental need for stable knowledge structures: a coherence that provides us with the equilibrium to function with purpose and action (Janoff-Bulma, 1989; Panksepp & Biven, 2012).

Notably, interpretation can be seen as a structural growth process that only begins in the second year of life when the Self beings to fathom Others and the World as separate and different (Siegel, 2012). With this in mind, one can begin to conceptualise this structure-function connexion as that which adaptively allows the Self to interpret and conceive a syllogistically reasoned schematic understanding of the World as it pertains to a syntactical and action-orientated Self or Other(s) (McGilchrist, 2009; Siegel, 2012).

To this end I finally define and enumerate interpretation as a notable faculty that, as it represents an explicit regulatory means to meet the embedded energy and information of the right hemisphere, is an assumptive form of operational knowledge which can, in times of stress, serve defensive and self-protective functions. Indeed, if over the course of life the Self has emerged in disintegrated and dysregulated manners and become reliant on protective forms of regulation, the Self will begin to make sense of what it senses (Thompson, 2021) through components of cognitive organisation predisposed toward individualistic, impersonalised, diagnostic, comparative, competitive, strategic, imitative, measured, bound, and decontextualised assemblages (McGilchrist, 2009; Siegel, 2012; Teyber & Teyber, 2017).

That is, the left hemisphere becomes dominant and begins to develop linguistical schematic suppositions that may reflect and perpetuate patterned ways of re-presenting, categorising, and evaluating experience with maladaptive bias (McGilchrist, 2009; Teyber & Teyber, 2017).

Conversely, if over the course of life Self has emerged in integrated and regulated manners – if the Self has become aware that one can trust an Other for a felt sense of security, the Self will begin to make sense of what it senses through components of cognitive organisation predisposed toward creating coherent narratives: the linear telling of a sequence of events that entails a focus on awareness, intention-to-act, verbal communication, meaning, and engagement of the individuals of the story, including the Self as narrator (Panksepp & Biven, 2012; Siegel, 2012). This is a rich base for resilience and the capacity of the Self to create contextual expressions of identity – an integrated sense of Self that is connected spatiotemporally (Badenoch, 2018; Siegel, 2012). That is, throughout the lifespan the Self can continue to surmise and re-present an understanding of the here-and-now (present) as it relates to the then-and-there (past) and the new-and-next (future) in compassionate, engaged, discerned manners.

And, as aforementioned, whilst this notion may be complex, it is with a nuanced understanding of this innate, interacting physiology that we become more able to attune to the subtle aspects of sensation (in Self and of Other), linking them to our perceptions and interpretations (of Self, Other, and World), and to respond to such with connected awareness, intention, and meaning.