Since the dawn of human civilization, injuries, infections and other historically identified ailments have been prevalent concerns for the individual and the masses. Indeed, ancient texts speak of humans as holistic beings whereby body, mind, spirit and kinship work harmoniously to create an integrated inherent balance that can be reflected as holistic wellbeing; ailments prevail when the holistic being is out of balance. Conversely, when the scientific revolution unfolded it began to stress a separation of this delicate biological, psychological and sociological balance that, despite research and discourse effort toward the contrary, still dominates western society (Sarafino, Caltabiano, & Byrne, 2008). Indeed, upon critical analysis of the statement “Health and wellness is more than the absence of disease. Therefore being in a state of health and wellness requires more than medical treatment” (see also World Health Organization, 2018) in relation to a biopsychosocial perspective, it was found that the biomedical model influences a majority of responses by individuals and society. This bringing an awareness to multiple paradoxes in modern approaches to holistic wellbeing. Further, through an overview of identification factors of, and general responses to, health and wellness issues in combination with identification and response practices to infertility in western society, it is acknowledged that biopsychosocial issues such as infertility reflect a post-renaissance trichotomous reaction based in disintegrated objective data.

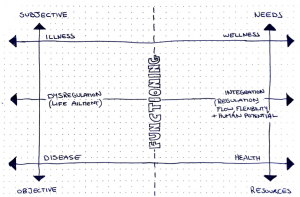

Though the use of the terms health, wellness, disease and illness at first seem unambiguous, without clarification these terms may be confused as either interchangeable or opposed to each other (Sarafino, Caltabiano, & Byrne, 2008; Ross & Kleman 2018). Most significantly is the less understood notion of the illness-wellness continuum. Representing a range of subjective experiences, the illness to wellness continuum indicates feelings of either balance or imbalance in which signs and symptomology lead to directed intention, potential diagnosis and prognosis, as well as reparative action (Helman, 1981; Boyd, 2000; Sarafino, Caltabiano, & Byrne, 2008; Ross & Kleman, 2018). Furthermore, in the scope of subjective experience, the illness to wellness continuum takes on a needs-resources based perspective that incorporates biopsychosocial functioning (Ross & Kleman, 2018).

Conversely, health and disease represent an inclination towards an impartial perspective. While these two terms are not entirely antonymous to each other, they are within a pathological spectrum that requires objective data to assess their validity (Helman, 1981; Boyd, 2000; Ross & Kleman, 2018). Meaning, disease is an ecological perspective highlighting a divergence from the biological norm (Helman, 1981; Ross & Kleman, 2018). And health, while still interconnected with the term “wellness”, incorporates a measurable objective perspective of, often with sociological and cultural bias, a neutral state of functional normality (Boyd, 2000; Myers & Sweeny, 2008; Ross & Kleman, 2018). With these definitions outlined, the need for an all-encompassing biopsychosocial model whereby “…being in a state of health and wellness requires more…” becomes evident.

As such, a new level of comprehension that incorporates the aforementioned definitions as they relate to an integrated inherent balance is comprised in Figure 1 . This then, opens discussion toward why health and wellness, and inarguably integration, is more than “absence”, requires more than “medical treatment”, and indeed involves an interplay of factors that impact holistic wellbeing.

Crucial to the holistic wellbeing of an individual are factors pertaining to traits and propensities (Siegel, 2010). That is, malleable patterns of reaction or response created over the lifespan have an impact on multiple areas of an individual’s life (Siegel, 2012 pp. AI-81 & AI-82). Such patterns comprise interrelating factors of an individual’s biological and physiological systems; psychological, philosophical, and spiritual schemas; as well as environmental, cultural, and sociological influenced sense-making (Myers & Sweeny, 2008; Sarafino, Caltabiano, & Byrne, 2008; Siegel, 2010). Combined, these factors result in variable virtues of personality and lifestyle, as well as relational and community-based choice or behaviour (Peterson, 2006; Myers & Sweeny, 2008; Sarafino, Caltabiano, & Byrne, 2008; Siegel, 2010). An exemplification of these impactful biopsychosocial factors is overt in the life “dysregulating” (Siegel, 2012, p. AI-25) ailment of infertility.

Designated by the International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) in the revised glossary of ART terminology, infertility is “a disease of the reproductive system defined by the failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse” (Zegers-Hochschild et al., 2009). Explicit in this definition is the objective diagnostic language that conveys an importance toward biological and physiological factors. Such factors may incorporate genetic abnormalities, age, as well as gender-specific issues of the reproductive system (Watkins & Baldo, 2009). Additionally, past infectious or environmental agents that have led to permanent dysfunction, such as STD caused tubal scaring; chronic diseases such as diabetes, cancer or autoimmune disorders; as well as a physical stress reaction to the frustration of an unmet desire, are contributory to the infertility diagnosis (Watkins & Baldo, 2009; Gerrity, 2001; Macaluso et al., 2010). Accordingly, this indicates the lifestyle / personality / physiology overlap, bringing awareness to a much broader and correlated biopsychosocial perspective.

Within this broader biopsychosocial perspective of infertility, contributory and perpetuating factors of prominence include: the meaning attributed to child rearing by one or both of the individuals within the couple; the sexual orientated beliefs or behaviours of the couple; the religious and/or cultural beliefs of the couple and their families; as well as a psychological toll that exists from many emotional and motivational contributory factors (Watkins & Baldo, 2009; Gerrity, 2001; Macaluso et al., 2010; Geller, Nelson, Bonacqisti, 2012; Nowoweiski, 2012). This highlights a profound complexity to infertility that has not been encapsulated within the objectified diagnostic ICMART/WHO definition. Furthermore, when infertility by definition is placed in context of the broader WHO definition of health (see World Health Organization, 2018) it begins to unfold paradoxes within the health industry.

Correspondingly, these complex and multifaceted factors within the broader perspective of infertility suggest that while a biomedical model may be the prominent antecedent to this life ailment, it is credible for psychosocial factors to be the main contribution, and indeed perpetuate the illness. For example, in theory, without sociocultural psychological pressure and an assumed association of child rearing with fulfilling positive life potential; or without attachment to generativity, femininity, or masculinity to fertility, emotional distress may not as impulsively lead to the assumption of “disorder” (Gerrity, 2001; Watkins & Baldo, 2009; Macaluso et al., 2010; Geller, Nelson, Bonacqisti, 2012; Nowoweiski, 2012). Consequently a less hastened reaction, based in an ideology of holistic wellbeing, may postpone a biomedical approach and allow for a broader and more complete response to infertility. So too, a less hastened response to illness in general may provide less paradoxical approaches to holistic wellbeing within the sociopolitical-economic health care system (Sarafino, Caltabiano, & Byrne, 2008; Kirsch 2018). This opens discussion to the impact of more general responses to health and wellness issues within society.

With the turn of the century, research into areas of happiness, positive psychology, interpersonal neurobiology, and holistic wellbeing within politics, the economy, and government policy made significant changes to response discourse and legislation (Peterson, 2006; Myers & Sweeny, 2008; Sarafino, Caltabiano, & Byrne, 2008; Siegel, 2010). However, there are still very predominant practical responses to illness and disease, both individual and sociocultural, that are based in sociopolitical-economical cost-benefit public healthcare systems (Sarafino, Caltabiano, & Byrne, 2008; Kirsch 2018). As a result, emphasis of public awareness and preventative measures to illness and disease within healthcare systems are often found to be made when costs of illness and disease provoke a burden on the sociopolitical-economic budget for medical treatment (Kirsch, 2018). As such, this raises the question: are predominant practical responses to illness and disease truly based in the efforts of the holistic wellbeing of individuals and societies?

No better exemplification exists of this notion than in infertility, or general responses to fertility and promiscuity. Over the past half century, sociocultural trends in family planning, women’s health and general sexual health have increased awareness of preventative measures for pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases/infections and adverse sexual behaviours (Hayes, 1987; Sarafino, Caltabiano, & Byrne, 2008; French, 2009; True, 2015; Qld Government, 2018). This response established primary preventative measures against the sociopolitical-economic burden of unintended pregnancy, infectious disease and sexual health behaviour, based in sociocultural education and biomedical behavioural response models (Sarafino, Caltabiano, & Byrne, 2008; Qld Government, 2018). Yet within the particulars of this response to fertility (see Hayes, 1987; Sarafino, Caltabiano, & Byrne, 2008; French, 2009; True, 2015; Qld Government, 2018 for specific responses), it can be seen that hastened policy responses often fail to incorporate a biopsychosocial perspective of holistic wellbeing over the lifespan (Family Planning Alliance Australia, 2008; Qld Department of Health, 2011). Accordingly, this may have the potential to alter beliefs and behaviours of individuals that may impede awareness of infertility prevention or fertility preservation (Macaluso et al., 2010; Department of Health, 2011; Garcia, Vassena, Prat, & Vernaeve, 2015), demonstrating that general responses to health and wellness issues do not accommodate integrated inherent balance.

Despite this, and in lieu of primary and secondary preventive measures, infertility takes on tertiary preventive measures within the biopsychosocial perspective (Sarafino, Caltabiano, & Byrne, 2008; Macaluso et al., 2010). Meaning, responses to the issue of infertility generally occur after unofficial psychological reactions to the inability to conceive, plus an official medically-based diagnosis procedure. Furthermore, due to the medicalisation of infertility (Nowoweiski, 2012), behavioural responses predominantly reflect biomedical interventions such as assisted reproductive technologies (Gerrity, 2001; Nowoweiski, 2012; Geller, Nelson, Boncquisti, 2012); thus indicating that while there may be discourse towards “…a state of health and wellness requires more than medical treatment”, a distinct biomedical model still dominates treatment within western society.

Correspondingly, although literature stresses the importance of psychological responses to infertility (Gerrity, 2001; Watkins & Blado, 2004; Macaluso et al., 2010; Nowoweiski, 2012), psychotherapy may elude the individuals receiving medical treatment due to the lack of legislation requirement (Blyth, 2012; see also Fertility Society of Australia, 2014 for the Code of Practice for Assisted Reproductive Technology Units). Such elusive responses may include various methodologies of psychotherapy based in: pain management; stress, coping and communication; grief and loss; self-acceptance, identity and a sense of control; positive meaning attribution and sense making; future orientation; as well as connection and normalization of the illness through group therapy (Gerrity, 2001; Watkins & Baldo, 2004; Nowoweiski, 2012; Geller, Nelson, Boncquisti, 2012). This further exemplifies the impact of biopsychosocial factors in infertility, why holistic wellbeing is more than an “absence of disease” that requires more than “medical treatment”, and the need for broadened general responses. Indeed, through a complete biopsychosocial perspective of infertility, as it relates to the picture of health and wellness in western society, it is evident that multifaceted approaches to holistic wellbeing need to surpass research and discourse and enter educational and professional settings.

With this comprehensive analysis and evaluation in mind, the imperative need for transparency and linkage within the differentiated areas of health and wellness issues becomes clear. Through clearly defining terminology, identifying biopsychosocial factors that impact health and wellness issues, and by exemplifying the nature of contributory biopsychosocial factors in infertility, it was shown that there is a perplexing paradox that exists between research, discourse, education and response practice. Furthermore, this underscored the question: are general and predominant practical responses to illness and disease truly based in the efforts of the holistic wellbeing of individuals and societies? Correspondingly, reflection on the nature of biopsychosocial responses to issues such as infertility confirmed that a biomedical model still dominates treatment. Finally, it can be identified that while the proclamation “Health and wellness is more than the absence of disease. Therefore being in a state of health and wellness requires more than medical treatment” is indeed true; it is proposed that, in general, as long as sociopolitical-economical based health promotion exists, so too will trichotomous responses based in a system of objectified, diagnostic and disintegrated biomedical models.

References

Blyth, E. (2012). Guidelines for infertility counselling in different countries: Is there an emerging trend? Human Reproduction, 27(7), 2046-2057. doi:10.1093/humrep/des112

Boyd, K. M. (2000). Disease, illness, sickness, health, healing and wholeness: exploring some elusive concepts. Medical Humanities, 26(1), 9-17. doi:10.1136/mh.26.1.9

Family Planning Alliance Australia. (2008). Time for a national & reproductive health strategy for Australia: Call to action. Retrieved from http://familyplanningallianceaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Time-for-a-national-srh-strategy-call-to-action.pdf

Fertility Society of Australia. (2014). Code of practice for assisted reproductive technology units. Retrieved from https://www.fertilitysociety.com.au/wp-content/uploads/RTAC-COP-Final-20141.pdf

French, K. (2009). Sexual health. Oxford, United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell.

García, D., Vassena, R., Prat, A., & Vernaeve, V. (2015). Increasing fertility knowledge and awareness by tailored education: a randomized controlled trial. Reproductive BioMedicine Online, 32(1), 113-120. doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.10.008

Geller, P. A., Nelson, A. R., & Bonacquisti, A. (2013). Women’s health psychology. In I. B. Weiner, A. M. Neuz, C. M. Neuz, & P. A. Geller (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Volume 9 (pp. 477-511). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Gerrity, D. A. (2001). A Biopsychosocial Theory of Infertility. The Family Journal, 9(2), 151-158. doi:10.1177/1066480701092009

Hayes, C. O. (1987). Risking the future: Adolescent sexuality, pregnancy, and childbearing. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Helman, C. G. (1981). Disease versus illness in general practice. Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1972172/pdf/jroyalcgprac00105-0038.pdf

King, L. A., Eells, J. E., & Burton, C. M. (2004). The good life, broadly and narrowly considered. In P. A. Linley & S. Joseph (Eds.), Positive psychology in practice (pp. 35-54). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Kirsch, D. E. (2017). Health policy and the delivery system. In C. L. Edelman, C. L. Mandle, & E. C. Kudzma (Eds.), Health promotion throughout the life span (9th ed., pp. 47-83). St Louis, MI: Elsevier.

Macaluso, M., Wright-Schnapp, T. J., Chandra, A., Johnson, R., Satterwhite, C. L., Pulver, A., … Pollack, L. A. (2010). A public health focus on infertility prevention, detection, and management. Fertility and Sterility, 93(1), 16.e1-16.e10. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.046

Myers, J. E., & Sweeney, T. J. (2008). Wellness counseling: The evidence base for practice. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86(4), 482-493. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2008.tb00536.x

Nowoweiski, S. (2013). Psychological implications of infertility and assisted reproductive technologies. In M. L. Caltabiano & L. Ricciardelli (Eds.), Applied topics in health psychology (pp. 185-198). Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

Peterson, C. (2006). A primer in positive psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Qld Department of Health. (2011). Department of Health | Sexual and reproductive health. Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/womens-health-policy-toc~womens-health-policy-experiences~womens-health-policy-experiences-reproductive

Qld Government. (2018). Sex education | Parents and families | Queensland Government. Retrieved from https://www.qld.gov.au/families/education/pages/sex

Ross, R., & Kleman, C. C. (2018). Health defined: Health promotion, protection, and prevention. In C. L. Edelman, C. L. Mandle, & E. C. Kudzma (Eds.), Health promotion throughout the life span (9th ed., pp. 1-22). St Louis, MI: Elsevier.

Sarafino, E. P., Caltabiano, M. L., & Byrne, D. (2008). Health psychology: Biopsychosocial interactions (2nd ed.). Brisbane, Qld: John Wiley & Sons.

Siegel, D. J. (2010). The mindful therapist: A clinician’s guide to mindsight and neural integration. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co.

Siegel, D. J. (2012). Pocket guide to interpersonal neurobiology: An integrative handbook of the mind. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

True. (2018). Health information. Retrieved from http://www.true.org.au/Reproductive-health/health-information

Watkins, K. J., & Baldo, T. D. (2004). The infertility experience: Biopsychosocial effects and suggestions for counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 82(4), 394-402. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2004.tb00326.x

World Health Organization. (2018). Constitution of WHO: principles. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/about/mission/en/

Zegers-Hochschild, F., Adamson, G., De Mouzon, J., Ishihara, O., Mansour, R., Nygren, K., … Vanderpoel, S. (2009). The International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) Revised Glossary on ART Terminology, 2009. Human Reproduction, 24(11), 2683-2687. doi:10.1093/humrep/dep343