Contents of Article

- 1 A Counselling conceptualisation and intervention based on a Wheel of Wellness.

- 1.1 A biopsychosocial model of well-being: Domains of the integrated self

- 1.2 Suffering and the perpetuating effects of pain and stress on well-being. An exemplification of a Wheel of Wellness conceptualisation

- 1.3 A biopsychosocial model of Holistic Well-being: Therapeutic interventions based on a Wheel of Wellness Conceptualisation

- 1.4 Conclusion

A Counselling conceptualisation and intervention based on a Wheel of Wellness.

Though often it may not be recognised as such, suffering – psychological, physiological, and even cultural – is an entity: an energy that exists within and between the dimensions of human wholeness. This energy is an enigma with a sometimes-subtle capacity to promote optimal functioning by way of enhanced adaptability and resilience (Sarafino, Caltabiano, & Byrne, 2008; Siegel, 2012). Yet, quite often this evolutionary emergent quality of flourishing in spite of suffering (Hall, Langer, McMartin, 2010) is unattainable. What then, within the counselling paradigm, opens opportunities for adaptability and resilience – and thus integrated well-being – in the face of suffering?

This paper proposes that attending to the energy and the potentially pervasive patterns of symbolic subjective meaning (Siegel, 2012) that arise from suffering, within a counselling paradigm that incorporates a biopsychosocial perspective of integrated well-being, opens opportunities for adaptability and resilience. To begin this analysis, a biopsychosocial modality of conceptualisation and therapeutic intervention known as a Wheel of Wellness (WoW) (see Appendix A), will be revealed. Thereafter, the WoW will be employed in a case study (see Appendix B) whereby the client, Jason, seeks counselling after a vehicle crash. An analysis through the WoW will highlight the impact of the crash and resulting whiplash, as well as the perpetuating effects of pain and stress (suffering). Furthermore, it will be shown how, within the counselling paradigm, a more in depth conceptualisation of the client begins to unfold directionality in intervention, opens opportunity for the client to find resolve in the presented issues, and exposes the client to a practice that enhances integrated well-being.

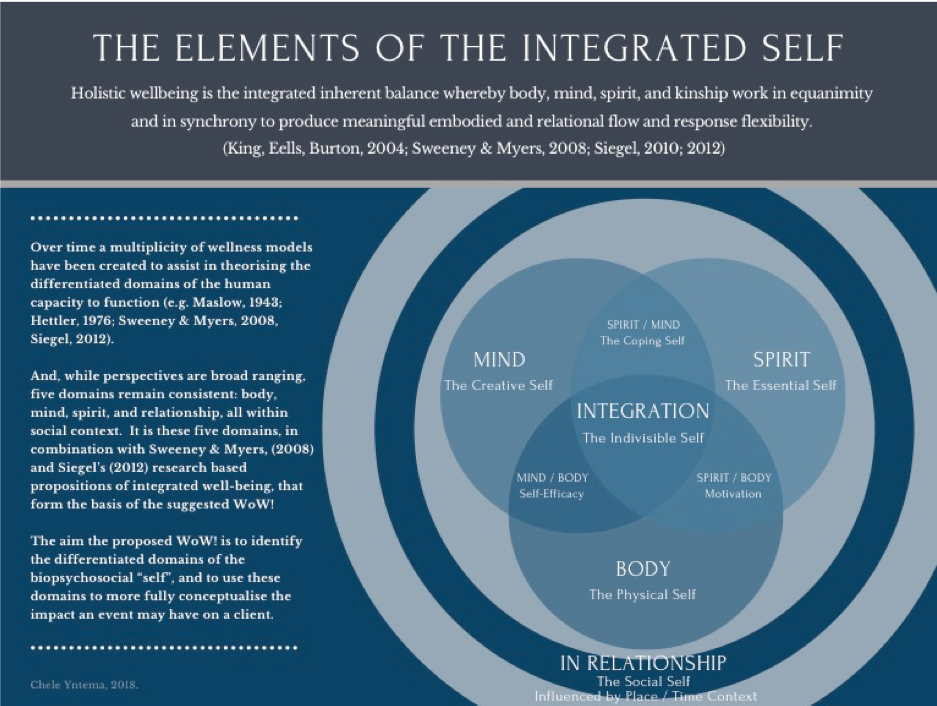

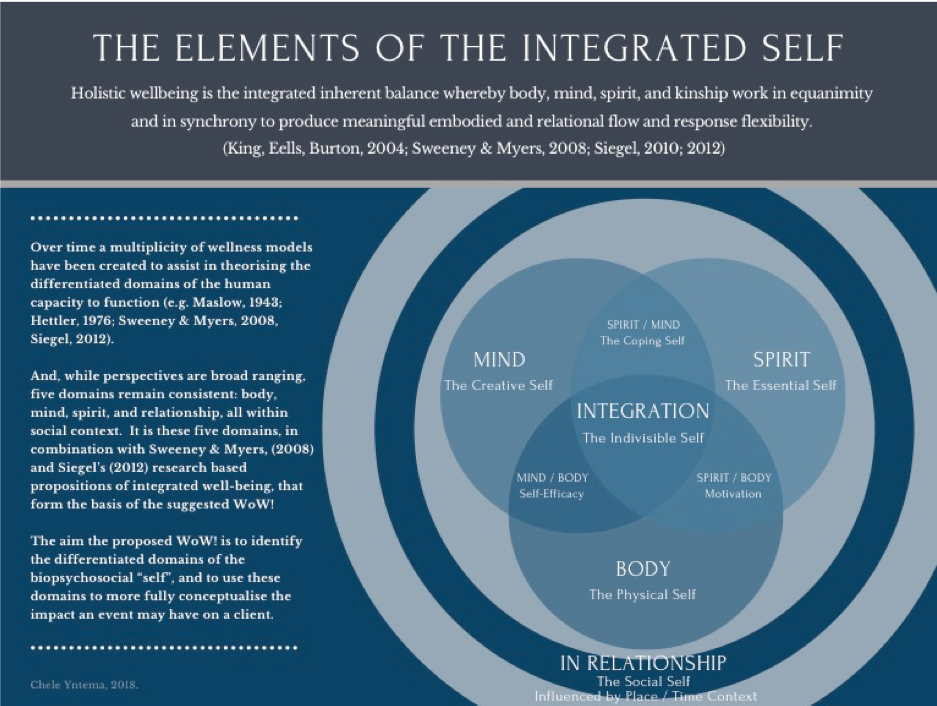

Within a counselling paradigm that seeks to create a space for a client to work with their suffering and discover their unique integrated inherent balance, a biopsychosocial conceptualisation of the “self” is fundamental. As such, over time a multiplicity of wellness models have been created to assist in theorising the differentiated domains of the human capacity to function (e.g. Maslow, 1943; Hettler, 1976; Sweeney & Myers, 2008, Siegel, 2012). And, while perspectives are broad ranging, four domains remain consistent: body, mind, spirit, and relationship, all within social context. It is these five domains, in combination with Sweeney & Myers, (2008) and Siegel’s (2012) research-based propositions of integrated well-being, that form the basis of the suggested WoW (Appendix A). The aim the proposed WoW is to identify the differentiated domains of the biopsychosocial “self”, and to use these domains to more fully conceptualise the impact an event may have on a client. Moreover, the aim of the WoW is to open opportunities for mindfully attending to the energy and the potentially pervasive patterns of symbolic subjective meaning (Siegel, 2012) that arise from suffering (King, Eells, Burton, 2004; Sweeney & Myers, 2008; Siegel, 2010, 2012). These objectives are vital within a counselling paradigm as the WoW enables a therapist to empower a client towards self-initiated adaptability and resilience through the overt linkage of the differentiated domains of the “self” (Siegel, 2012).

Within a counselling paradigm that seeks to create a space for a client to work with their suffering and discover their unique integrated inherent balance, a biopsychosocial conceptualisation of the “self” is fundamental. As such, over time a multiplicity of wellness models have been created to assist in theorising the differentiated domains of the human capacity to function (e.g. Maslow, 1943; Hettler, 1976; Sweeney & Myers, 2008, Siegel, 2012). And, while perspectives are broad ranging, four domains remain consistent: body, mind, spirit, and relationship, all within social context. It is these five domains, in combination with Sweeney & Myers, (2008) and Siegel’s (2012) research-based propositions of integrated well-being, that form the basis of the suggested WoW (Appendix A). The aim the proposed WoW is to identify the differentiated domains of the biopsychosocial “self”, and to use these domains to more fully conceptualise the impact an event may have on a client. Moreover, the aim of the WoW is to open opportunities for mindfully attending to the energy and the potentially pervasive patterns of symbolic subjective meaning (Siegel, 2012) that arise from suffering (King, Eells, Burton, 2004; Sweeney & Myers, 2008; Siegel, 2010, 2012). These objectives are vital within a counselling paradigm as the WoW enables a therapist to empower a client towards self-initiated adaptability and resilience through the overt linkage of the differentiated domains of the “self” (Siegel, 2012).

Suffering and the perpetuating effects of pain and stress on well-being. An exemplification of a Wheel of Wellness conceptualisation

Recently experiencing a vehicle crash, Jason is seeking assistance through counselling (see Appendix B). Initial understanding through the domains of the WoW highlight that an environmental event placed demands on Jason’s systems whereby a lack of resources impeded an inherent ability to return to normal functioning (Sarafino et al., 2008; Kubzansky & Winning, 2016). Due to the nature of the acceleration to rapid deceleration movement (Ritchie, Ehrlich, & Sterling, 2017) involved in the crash, Jason was left with an encumbering injury to his neck and shoulders known as whiplash. In a whiplash injury the physical stress placed on the muscular, skeletal, immune, and nervous system present a complexity of systematic responses (e.g., Sandlund et al., 2006; Chien, Eliav, Sterling, 2009; Ritchie et al, 2017). When combined these responses are known as whiplash-associated disorders (WAD) (Sandlund et al., 2006) and present a set of symptoms that, unless attended to during the acute phase, become chronic (Sandlund et al., 2006; Mariotti, 2015; Siegel, 2012). Moreover, in conceptualising Jason’s case, it seems this physiologically-based reaction has likely begun a cycle of pain and stress that is impeding functioning within multiple domains, creating perpetual effects.

With this same WoW conceptualisation, and analogous to the cycle of physiological stress and pain that currently impedes functioning within Jason’s life, is the cycle of the psychological and interpersonal stress and pain that prevents Jason’s ability for adaptability and resilience in spite of suffering. The psychological aspect of Jason’s suffering may be highly prejudiced by the reaction to the crash from both his work environment, namely the interpersonal interactions and communication he has with his boss, as well as by the levels of compassionate support from his wife. Devaluation of the subjective experience has the potential to create dysregulated defensive reactions (Siegel, 2012) based in feelings of a lack of control and inadequate problem solving skills; an incapacity to take responsibility for healing due to the inability to make sense of the event(s); perceptions of judgment, deficiency, helplessness, and worthlessness; as well as a potential perception that expressing authentic emotional ebb and flow is unwarranted or unaccepted (Sweeney & Myers, 2008; Sweeny, 2009). These dysregulated defensive reactions demonstrate the impact of the crash on self-efficacy and motivation. Furthermore, these reactions deplete internal resources and the self-regulating skills required to enable a sense of coping (Sarafino et al., 2008; Siegel, 2012; Maddux & Gosselin, 2014; Scarantino, 2014). Additionally, due to the inherently interrelated nature of the psyche to physiology (Mariotti, 2015), these reactions may appear as prolonged stress and sick-role behaviours (Sarafino et al., 2008; Turk & Robinson, 2011) and further perpetuate the pain and stress cycle. To summarise, the impact of the crash on the various domains of “self” has led Jason to the cusp of falling prey to a prognosis of chronic WAD suffering. Without intervention his stress and pain will continue, causing enduring dysregulation (Ritchie et al., 2017); this summarisation further demonstrating how acknowledging biopsychosocial factors through the use of the WoW opens an initial evidence-based understanding of Jason that can direct opportunities for building adaptability and resilience.

With a basic conceptualisation made, and with an appreciation that the client presents seeking specific treatment outcomes, therapeutic intervention within specific domains of the WoW can address the need for a deepening awareness of the energy and the potentially pervasive patterns of symbolic subjective meaning (Sarafino et al., 2008; Siegel, 2010, 2012; Ritchie et al., 2017; Sarrami et al., 2017). As such, and due to the nature of the crash and the impeding factors within Jason’s relationships, it is vital to establish a non-judgmental atmosphere (Siegel, 2012). Validation of the event, the injury, and the treatment required, as well as validation of subjective interpretations are imperative in laying foundations for integration (Siegel, 2012; Turk & Robinson, 2011). With this in mind, it is proposed that a sense of trust be established through an active listening basis of history taking: attuned, resonating appreciation of the subjective experiences, as well as formal biopsychosocial assessment that considers objective data (Sweeney, 2009; Siegel, 2010; Andrasik, Buse, & Lettich, 2014; Belar & Deardorff, 2015), opens opportunity for in-depth understanding of Jason’s past and present. With trust, Jason will begin to see that his pain and stress is believed, understood, and a legitimate reaction (Ritchie et al., 2017) to the events that unfolded. This foundation of non-judgmental validation and self-compassion may then open opportunities for Jason to learn skills that reestablish a sense of clarity and control, and motivate him to find resolve within his own internal resources – a foundational mechanism to adaptability and resilience, as based in integrated well-being.

Secondly, moving towards adaptability and resilience, and in addressing more overt predominant factors, such as the perpetuating pain and stress within Jason’s case, a focus on mindful awareness may begin to make change possible (Siegel, 2012). The fundamental nature of the crash and injury means that Jason most likely has experienced an altered sense of sensation within his peripheral nervous system (Sandlund et al., 2006), an effect on his central nervous system, as well as an altered immune system (Sarafino et al., 2008; Chien, et al., 2009); these in turn affect proprioception (Sheets-Johnstone, 2012), neuroception (Porges, 2007), and thus subjective sense-making (Siegel, 2012) within all domains of the WoW. With this in mind, therapeutic interventions may comprise of western and eastern-based practices that attend to the interrelated nature of Jason’s pain and stress, while at the same time attending to his primary request for managing computer use and the resulting neck pain. These intervention suggestions include, yet are not limited to: Biofeedback (Aritzeta et al., 2017); the Wheel of Awareness (Siegel, 2010, 2012); body centred mindfulness (Caldwell, 2012), mindful meditation (Hamilton, Kitzman & Guyotte, 2006), or Tonglen (Girijananda, 2015); and yoga (Cortright, 2007; van der Kolk, 2014; Seigel, 2012). Each of these therapeutic modalities attends to the breath as a basis of relaxation and a mindful awareness of the connectivity between the physically felt energy and associated patterns of symbolic subjective meaning (Siegel, 2012). Moreover, these integral modalities begin to create self-regulation as well as pain and stress management; thus building upon the coping self, which in turn promotes enduring adaptability and resilience.

In addition to building adaptability and resilience through mindful awareness, it is vital to address the relational nature of Jason’s stress. Empowering Jason with an understanding of assertion that incorporates receptive interpersonal communication skills will build a basis for more practical applications that address multiple relational circumstances (Abigail & Cahn, 2011; Museux Dumont, Careau, & Milot, 2016; Rosenberg, 2015). For example, within the work environment assertion may enable Jason to clarify his medical needs and express his feelings of devaluation. Furthermore, interpersonal communication skills will potentially open opportunities within the home environment for problem resolution (finances for example) based in compassionate communication and meaning-making (The Gottman Institute, 2018). Overall, these skills offer Jason an underlying sense of efficacy and motivation that encapsulates more than present moment solutions. Once again, this highlights the value of a counselling paradigm that exposes a client to a practice that attends to all of the domains of “self” building adaptability and resilience, thus promoting integrated well-being.

Finally, it must not be negated that although these recommended practices that attend to the domains within the WoW that pertain to coping, self-efficacy, and motivation, as they relate to body, mind, and spirit are effective treatments within a counselling paradigm – they do not replace the need for biomedical based treatment such as medication, physiotherapy, and general practitioner appointments (Sarafino et al., 2008).

Conclusion

This paper proposed that a counselling paradigm that incorporates a biopsychosocial modality of conceptualisation such as the proposed Wheel of Wellness, opens opportunities for more effective therapeutic intervention. Through a case involving whiplash and the perpetuating effects of pain and stress (suffering), it was shown that in-depth conceptualisation of the client unfolds directionality in intervention; this then opening opportunity for the client to find resolve in the presented issues, as well exposing them to a practice that not only enhances adaptability and resilience, it promotes enduring integrated well-being.

To conclude, while the evolutionary emergent quality of flourishing in spite of suffering that is unique to each individual may never be comprehensively understood, domains within individuals that enhance the human capacity for adaptability and resilience are comprehensively researched and theorised. As such, with the use of a method of client conceptualisation and intervention that entails the four domains: body, mind, spirit, and relationship, all within social context, the client can be made aware, and attend to energy and potentially pervasive patterns of symbolic subjective meaning that arise in suffering, thus making the change needed for enduring integrated well-being.

References

Abigail, R. A., & Cahn, D. D. (2011). Managing conflict through communication (4th ed.).

Boston, MA: Pearson.

Andrasik, F., Buse, D. C., & Lettich, A. (2014). Assesment of headaches. In D. C. Turk & R.

Melzack (Eds.), Handbook of pain assessment (4th ed., pp. 354-375). New York, NY: Guildford Press.

Aritzeta, A., Soroa, G., Balluerka, N., Muela, A., Gorostiaga, A., & Aliri, J. (2017). Reducing anxiety and improving academic performance through a biofeedback relaxation training program. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 42(3), 193-202. doi:10.1007/s10484-017-9367-z

Belar, C. D., & Deardorff, W. W. (2015). Fundamentals of assessment in clinical health psychology. In F. In Andrasik, J. L. In Goodie, & A. L. In Peterson (Eds.), Biopsychosocial assessment in clinical health psychology. New York, NY: Guildford Press.

Caldwell, C. (2012). Sensation, movement, and emotion: Explicit procedures for implicit memories. In S. C. Koch, T. Fuchs, & M. Summa (Eds.), Body memory, metaphor and movement (pp. 255-266). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Chien, A., Eliav, E., & Sterling, M. (2009). Hypoaesthesia occurs with sensory hypersensitivity in chronic whiplash – Further evidence of a neuropathic condition. Manual Therapy, 14(2), 138-146. doi:10.1016/j.math.2007.12.004

Fuchs, T. (2012). The phenomenology of body memory. In S. C. Koch, T. Fuchs, & M. Summa (Eds.), Body memory, metaphor and movement (pp. 9-22). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing.

Girijananda, S. (2015). Tonglen for our own suffering: 7 Variations on an ancient practice. Portland, OR: Ruda Press.

The Gottman Institute. (2018). The sound relationship house archives – The Gottman Institute. Retrieved from https://www.gottman.com/blog/category/the-sound-relationship-house/

Hall, M. E., Langer, R., & Mcmartin, J. (2010). The role of suffering in human flourishing: Contributions from positive psychology, theology, and philosophy. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 38(2), 111-121. doi:10.1177/009164711003800204

Hamilton, N. A., Kitzman, H., & Guyotte, S. (2006). Enhancing health and emotion: Mindfulness as a missing link between cognitive therapy and positive psychology. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 20(2), 123-134. doi:10.1891/jcop.20.2.123

HeartMath Institute. (2018). Chapter 02: Resilience, stress and emotions. Retrieved from https://www.heartmath.org/research/science-of-the-heart/resilience-stress-and-emotions/

Hettler, B. (1976). The six dimensions of wellness model. Retrieved from http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.nationalwellness.org/resource/resmgr/pdfs/SixDimensionsFactSheet.pdf

King, L. A., Eells, J. E., & Burton, C. M. (2004). The good life, broadly and narrowly considered. In P. A. Linley & S. Joseph (Eds.), Positive psychology in practice (pp. 35-54). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Maddox, J. E., & Gosselin, J. T. (2014). Self-efficacy. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (2nd ed., pp. 198-224). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Mariotti, A. (2015). The effects of chronic stress on health: new insights into the molecular mechanisms of brain–body communication. Future Science OA, 1(3). doi:10.4155/fso.15.21

Maslow, A. H. (1943). Theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370-396. doi:10.1037/h0054346

Museux, A., Dumont, S., Careau, E., & Milot, É. (2016). Improving interprofessional collaboration: The effect of training in nonviolent communication. Social Work in Health Care, 55(6), 427-439. doi:10.1080/00981389.2016.1164270

Myers, J. E., & Sweeney, T. J. (2008). Wellness Counseling: The Evidence Base for Practice. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86(4), 482-493. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2008.tb00536.x

Porges, S. W. (2007). The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 116-143. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.009

Pyszczynski,, T., Greenberg, G., & Arndt, J. (2014). Freedom versus fear revisited: An integrative analysis of the dynamics of the defense and growth of self. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (2nd ed., pp. 378-404). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Ritchie, C., Ehrlich, C., & Sterling, M. (2017). Living with ongoing whiplash associated disorders: a qualitative study of individual perceptions and experiences. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 18(1), 1-9. doi:10.1186/s12891-017-1882-9

Rosenberg, M. B. (2015). Nonviolent communication: A language of life. Chicago, IL: Puddle Dancer Press.

Sandlund, J., Djupsjöbacka, M., Ryhed, B., Hamberg, J., & Björklund, M. (2006). Predictive and discriminative value of shoulder proprioception tests for patients with whiplash-associated disorders. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 38(1), 44-49. doi:10.1080/16501970510042847

Sarafino, E. P., Caltabiano, M. L., & Byrne, D. (2008). Health psychology: Biopsychosocial interactions (2nd ed.). Brisbane, Qld: John Wiley & Sons.

Sarrami, P., Armstrong, E., Naylor, J. M., & Harris, I. A. (2017). Factors predicting outcome in whiplash injury: a systematic meta-review of prognostic factors. Journal of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, 18(1), 9-16. doi:10.1007/s10195-016-0431-x

Scarantino, A. (2016). The philosophy of emotions and its impact on affective science. In L. F. In Barrett, M. In Lewis, & J. M. In Haviland-Jones (Eds.), Handbook of emotions(4th ed., pp. 3-28). New York, NY: Guildford Press.

Sheets-Johnstone, M. (2013). Kinesthetic memory: Further critical reflections and constructive analyses. In S. C. Koch, T. Fuchs, & M. Summa (Eds.), Body memory, metaphor and movement (pp. 43-72). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing.

Siegel, D. J. (2010). The mindful therapist: A clinician’s guide to mindsight and neural integration. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co.

Siegel, D. J. (2012). Pocket guide to interpersonal neurobiology: An integrative handbook of the mind. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co.

Siegel, D. J. (2017). Mind: A journey to the heart of being human. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co.

Sweeney, T. J. (2009). Adlerian counseling and psychotherapy: A practitioner’s approach(5th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Turk, D. C., & Robinson. (2014). Assessment of patients with chronic pain: A comprehensive approach. In D. C. Turk, R. Melzack, & Guilford Press (Eds.), Handbook of pain assessment (3rd ed., pp. 188-212). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: Mind, brain and body in the transformation of trauma. New York, NY: Viking.

In deconstructing the Wheel of Wellness (Figure 1 – WoW!), to begin it is crucial to identify the imperative nature of relationship. Humans are inherently relational creatures, born from relationship and into relationship (Siegel, 2012); therefore the WoW is encircled in the milieu of the social self (Sweeney & Myers, 2008). Meaning, within the macro and micro systems that govern our reality that are dependent on place and time, for an individual to obtain or reestablish the self-regulating skills required for integration, compassionate connections of trust and authenticity are crucial (Sweeney & Myers, 2008; Sweeney, 2009; Siegel, 2010, 2012).

Furthermore, in analyzing the WoW, although there are the inherently obvious factors of body, mind, and spirit, as described below, three further domains (Sweeney & Myers, 2008) directly influence the self-organizational and regulatory process’ (Siegel, 2012) that promote integration. The proposed concepts of “the coping self” (Sweeney & Myers, 2008; Sweeney, 2009), “self-efficacy” (Maddux & Gosselin, 2014), and “motivation” (Pyszczynski, Greenberg, & Ardt, 2014), more clearly articulated below, are the intrinsic combinations of mind to spirit, spirit to body, body to mind, that have the capacity to either impede or promote integration.

Relationship – The Social Self

As identified by Myers & Sweeney (2008) the social self is “Social support through connections with others in friendships and intimate relationships, including family ties” and includes friendship and love (p.485). To build on this, Siegel (2012) identifies relationship as “The patterns of interaction between two or more people that involve the sharing of energy and information flow” (p. AI-68).

– Influenced by Place / Time Context

As identified by Myers & Sweeney (2008) context includes local, institutional, global, and chronometrical (p.485). Again to build upon this notion, Siegel (2017) states, “Time, as we know it, may not exist. Time as something that flows, something we can run out of, something that we’re pressured to hold onto, is a mental construction, a self-created stress, an illusion of the mind. All we have, from these scientific and spiritual views, careful quantitative research, and contemplative investigating reflection, is now. And if now shapes not only when we are, but also where we are, and how we are, then what is now really made of?” (p.212)

Body – The Physical Self

Though this may seem to be the most basic element, paradoxically it is the most complex and interwoven element within the WoW. As identified by Myers & Sweeny (2008) “The [body is the] biological and physiological processes that compose the physical aspects of a person’s development and functioning” (p.485). The body as an interrelated and dependent element of optimal holistic wellbeing and as such and expanded view of the physical self includes an “implicit memory based on the habitual structure of the lived body, which connects us to the world through its operative intentionality. The memory of the body appears in different forms, which are classified as procedural, situational, intercorporeal, incorporative, pain, and traumatic memory. The life-long plasticity of body memory enables us to adapt to the natural and social environment, in particular, to become entrenched and to feel at home in social and cultural space.” (Fuchs, 2012, p.9).

Mind – The Creative Self

As identified by Myers & Sweeny (2008) the creative self is “The combination of attributes that each of us forms to make a unique place among others in our social interactions and to positively interpret our world”, this includes thinking, emotions, control, work, and positive humor (p.485). This notion of mind is further expanded by Siegel (2012) as “personal subjective experience, consciousness with a sense of knowing and that which is known, and a regulatory function… [a regulator of] the flow of energy and information” (p. AI-51).

Spirit – The Essential Self

As identified by Myers & Sweeney (2008) the essential self is “Essential meaning-making processes in relation to life, self, and others” and includes spirituality, identity, and self-care (p.485). To further enhance this definition, spirit can be seen as ones identity based in character traits: the propensities created over the lifespan and that pertain to non-matter beliefs. Spirit is also the inherent knowing of the un-worded energy within and between, and is the domain of responsibility for self and other wellbeing (Siegel, 2017).

Spirit / Mind – The Coping Self

As identified by Myers & Sweeney (2008) the coping self is “The combination of elements that regulate one’s responses to life events and provide a means to transcend the negative effects of these events” and includes leisure, stress management, self-worth, and realistic beliefs (p.483). This element of the integrated self also reflects components of inherent adaptability and the ability to create a more resilient self in the face of adversity (HeartMath Institute, 2018).

Mind / Body – Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy as based on Bandura’s (1997) original classification is defined by Maddux & Gosselin as (2014) “beliefs regarding one’s ability to exercise one’s competencies in certain domains and situations. Self-efficacy beliefs are not concerned with perceptions of skills and abilities divorced from situations; they are concerned, instead, with what people believe they can do with their skills and abilities under certain conditions. In addition, they are concerned not simply with beliefs about the ability to perform trivial motor acts but with the ability to coordinate and orchestrate skills and abilities in changing and challenging situations” (p.199).

Body / Spirit – Motivation

While closely related to the Mind / Body – Self-Efficacy domain, motivation is specifically defined here as the quality of “the known” and “the knowing” (Siegel, 2012, p. 1-3) of inner experience that drives action. A more physiological and biological based energy in motion that encapsulates “perceptions of skills and abilities divorced from situations” (Maddux & Gosselin, 2014, p.199) and abilities (Scarantino, 2014).

Appendix B

A Case Study

Jason is a 29 year old married man with one child who is 3 years old. He has been with his partner for over 10 years and married when they found out their son was on the way. Since then Jason has adjusted to being married, their new baby son, loss of income as his wife is caregiving their son full time and the recent purchase of a family home.

Two months ago Jason was involved in a car accident. His car was off the road for a month which made it difficult to get to and from work, but he managed. Jason had a whiplash injury which persists in creating pain and discomfort, especially if he uses his computer for too long without a break. His job involves entering sales and other data for the company and he is usually using the computer for several hours a day. As the accident was on his way home from work, he understands that the payment of lost wages and medical expenses will be covered through Workcover.

Jason’s supervisor has queried his claim for a week off after the accident as it was “only a minor accident so why did he need this time off?” He also has queried the fact that Jason has lost ten half days due to appointments at the doctor and physiotherapist. His supervisor assured him that the query came from the insurers, not him, but he has to ask Jason to explain this request.

Jason has expressed to his wife that he feels like the supervisor does not believe him about the impact of his injury and the insurers may not pay, and this has big implications for their finances. Needless to say Jason is feeling quite stressed about the situation and has come to you to discuss the matter. He also wants some ideas on how to manage computer usage and his neck pain.